Grocery Update #67: Feeding Wall Street While Starving Stores.

The Long-Term Harm From Short-Term Profits.

Feeding Wall Street While Starving Stores.

Coverage of Bullies At The Table: The Consequences of Understaffing by Kroger and Albertsons.

The Economic Roundtable, www.economicrt.org, Daniel Flaming and Patrick Burns. Summary Edited by Errol Schweizer.

Introduction/Context: Food Workers In Crisis.

By Errol Schweizer.

Thanks for tuning into this special feature of the Grocery Update, our coverage of Bullies at the Table, Understaffing by Kroger and Albertsons, a report by The Economic Roundtable about the financial and operational impacts of cost cutting at two of the largest U.S. grocery chains. This is heavy stuff, impacting hundreds of thousands of essential grocery workers across the U.S., and is a bellwether for what clerks, cashiers and retail staff are experiencing at many other grocery chains. The report was underwritten in part by unions representing 65,000 essential grocery workers. Their current contract expired on Sunday, March 2, 2025 and are fighting for “living wages, affordable healthcare benefits, a reliable pension and more staffing and better working conditions for a better customer experience”. The report is timely and strategic for these union members, but also important for the grocery sector as a whole, especially anyone working for a publicly traded grocer subject to the whims of asset managers and investors.

Bullies At The Table also picks up where a previous study of Kroger’s business model left off. This 2022 survey commissioned by UFCW found that over three quarters of Kroger workers were food insecure and 14% were housing insecure. These types of numbers are critical because Kroger, which owns Smith’s, QFC, King Soopers, Fred Meyer, Harris Teeter, Ralph’s and others, is the second largest grocery chain in the U.S. after Walmart, and the findings can be extrapolated to represent the state of grocery workers in general. It’s not a pretty picture.

At the time of the 2022 report, Kroger was well aware of the state of its employees, and chose not to address the crisis. A 2018 leaked internal Kroger report showed that hundreds of thousands of company workers relied on food stamps and other public benefits just to get by. The report quoted an employee saying, “I literally work at a grocery store and can’t afford to eat regularly.” Despite union-negotiated pay raises in recent years, most Kroger wages fall far below what constitutes a living wage for where their stores are located. Likewise for the comparable wages at most of Kroger’s competitors, such as Albertsons (Randall’s, Von’s, Acme, etc), Ahold-Delhaize (Stop & Shop, Food Lion, Hannaford, etc.), Walmart, Target, Whole Foods, HEB, Trader Joe’s, etc. To be food insecure and to work in grocery stores is quite normal in America.

The 2018 Kroger report noted that in their headquarters state of Ohio, Kroger had the third highest number of employees receiving public assistance, after Walmart and McDonald’s. The 2018 report also coincided with that year’s launch of Kroger Zero Hunger Zero Waste. The initiative partners with nonprofits such as Feeding America and Meals on Wheels. The internal Kroger source who leaked the 2018 report noted that the company was focused on suppressing wages while burnishing their public image in order to deliver the promised 8-11% returns for shareholders, which, based on the findings below, seems to have been a successful strategy for shareholders. It is also a deeply cynical strategy and no wonder why some critics call such philanthropic food assistance the “hunger industrial complex”, because it reinforces the economics that cause hunger in the first place.

A more recent survey by Food Chain Workers Alliance showed that the crisis of food insecurity and poverty among food workers is widespread and severe:

Compared to workers in other industries, frontline food workers are 68% more likely to live below the poverty line.

Food workers are more likely to be food insecure than workers in any other industry; food workers were 93% more likely to be food insecure than non-food workers, with nearly 1 in 5 frontline food workers being insecure.

Food workers are 60% more likely to rely on SNAP.

Since 2019, food insecurity rates rose 22% for the country as a whole, 33% for food workers, and 96% and 87% for food workers in distribution and processing sectors.

Frontline food workers continue to be among the lowest paid workers in the U.S., earning a median income of $28,000 per year.

Frontline food system workers are more likely to be women of color, people of color, and immigrants than the general workforce, and women in the food industry earn, on average, 66% of what men are paid.

Wage theft is a major problem across the food system, more than any other industry.

Or, think about it this way. Since the 1975, over $79 trillion in income was stolen from the bottom 90% of wage earners, as wages did not keep up with their productivity, or almost $4 trillion a year. The average income in the U.S. today is $74,000. Minus the top 10 earners, it’s $65,000. Minus the top 1,000, it’s just $35,500. Who can live off of $35,000 a year? Apparently, tens of millions of people in the U.S. do, including the majority of food workers.

These numbers don’t exist in a vacuum. They represent the lives, livelihoods, aspirations and struggles of the people who feed us, pick our crops, milk our cows, process our meat, manufacture our snacks, deliver our fish and vegetables, stock our shelves, ring us up at the register and sweep up after closing.

It is a crisis that every single person who works in any aspect of the food industry should prioritize, not just the blue collar rank and file staff who are essential to its functions, but-especially- the investors and executives who are earning at the highest income brackets in the sector and benefiting directly from this inequality. And it is a situation that neither political party has been willing or able to solve, and the Trump Republicans will likely make much worse.

But the solutions are right here at hand. They just require will power and organization to implement. Living wages, paid sick leave and child care, full staffing of stores, protecting the right to organize, expanding employee ownership, ensuring all food and farmworkers are fully protected by labor laws, etc. This isn’t rocket science.

Food workers-led organizations like Food Chain Workers Alliance as well as the rank and file-led UFCW chapters that sponsored the report below understand the problems and have solutions. They don’t need fair trade certifications, philanthropy, virtual signaling or hand-wringing. They need support and solidarity to win.

The Consequences of Understaffing by Kroger and Albertsons.

By Daniel Flaming, Patrick Burns, May 2025

The Economic Roundtable, www.economicrt.org

Edited and abridged for clarity.

Highlights and Conclusions.

Hard Times for Grocery Workers.

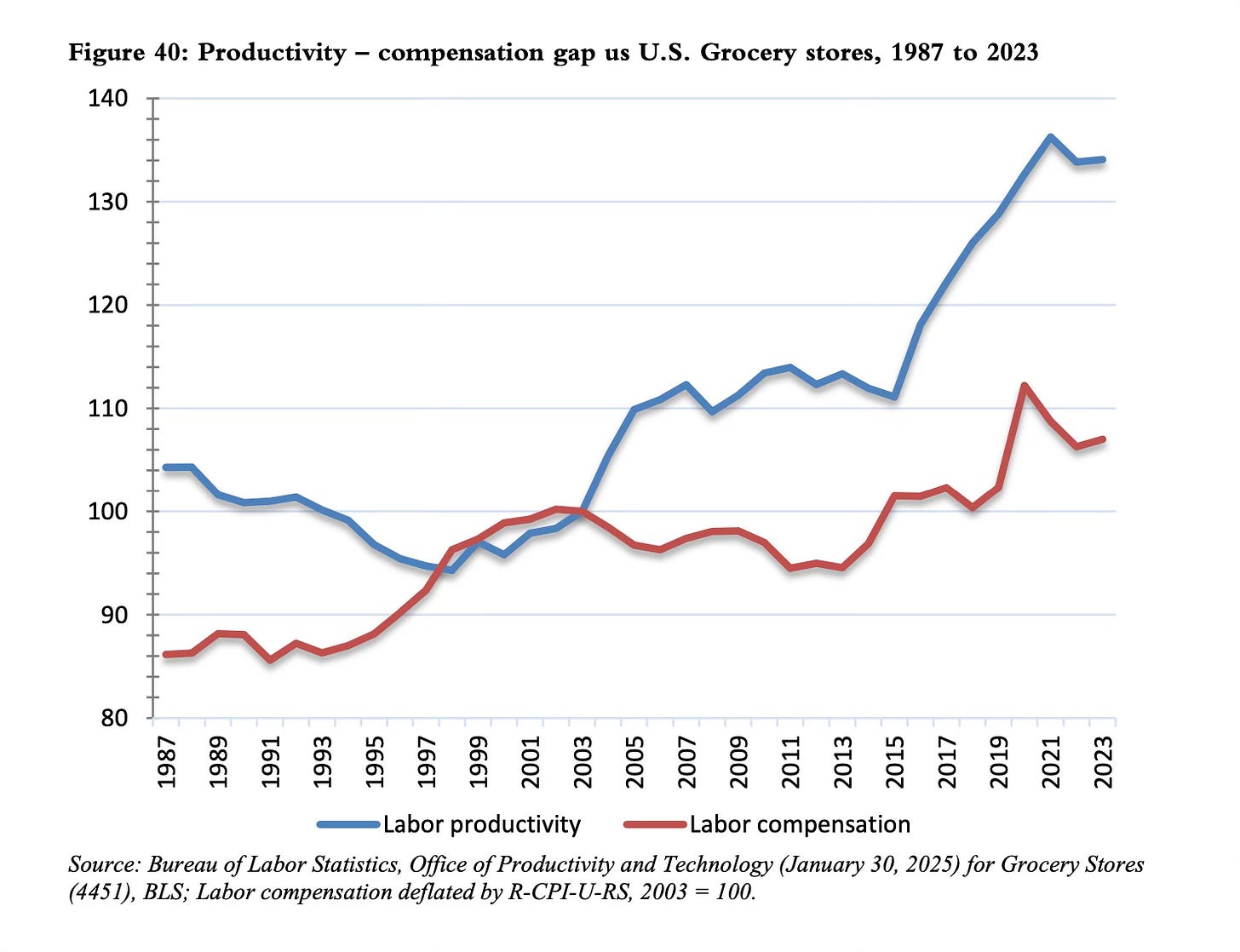

Grocery workers overwhelmingly agree that their pay does not fairly compensate them for their experience and work. They are 27 times more likely to agree that prices in their stores have increased faster than their wages, and that the amount of work they have to complete during their shift has increased. National data for the grocery store sector reveals an industry with a widening gap between labor productivity (real output per labor hour) and compensation. Compensation has also fallen behind productivity growth.

Workers see that they are the frontline of the food distribution system that puts food on people’s tables, but that they are not given recognition, support and compensation that is commensurate with their essential role.

Furthermore, they see that their company is profitable because of the work that they do. The grocery labor force lives with extreme financial insecurity. More than four-fifths of workers are unable to pay basic living costs. The consequence of the poverty wages received by many grocery workers is that more than two-thirds do not have secure housing.

More than nine out of ten grocery store workers in the three states report price gouging at their stores and that their company is raising prices higher than production costs. As a consequence, customers put groceries back on the shelf because they cannot afford to buy them and they are buying less balanced and healthy food than they used to. This means that public health is being adversely affected by inflated grocery prices.

Most grocery workers in California, Colorado and Washington who are represented by UFCW Locals 7, 324, 770, and 3000 say that product sits in their stores’ backrooms because there is not enough staff to stock store shelves and that their stores are unable to provide good customer service.

They say that they are unable to complete all of their assigned tasks during their shift. This means that most grocery customers are going into stores where tasks such as cleaning and stocking shelves are neglected.

Industry Consolidation.

The Southern California strike/lockout of 2003 and 2004 was a critical turning point in grocery industry labor conditions. Although the California Attorney General later accused the supermarket employers of engaging in illegal collusion, the ripple effects for local unions bargaining after the strike included lower pay, more workplace stress and unpredictable work schedules.

Kroger and Albertsons are industry giants. They employ 28 percent of U.S. grocery workers. Albertsons’ share is 11 percent, while Kroger’s share is 17 percent. Three decades of industry ownership concentration have tilted the playing field in favor of grocery giants, to the disadvantage of small brands and the workers who put food on the shelves in stores. The timing of the aggressive stance taken by grocery companies in 2003 followed a phase of significant consolidation among regional supermarket chains in the 1990s.

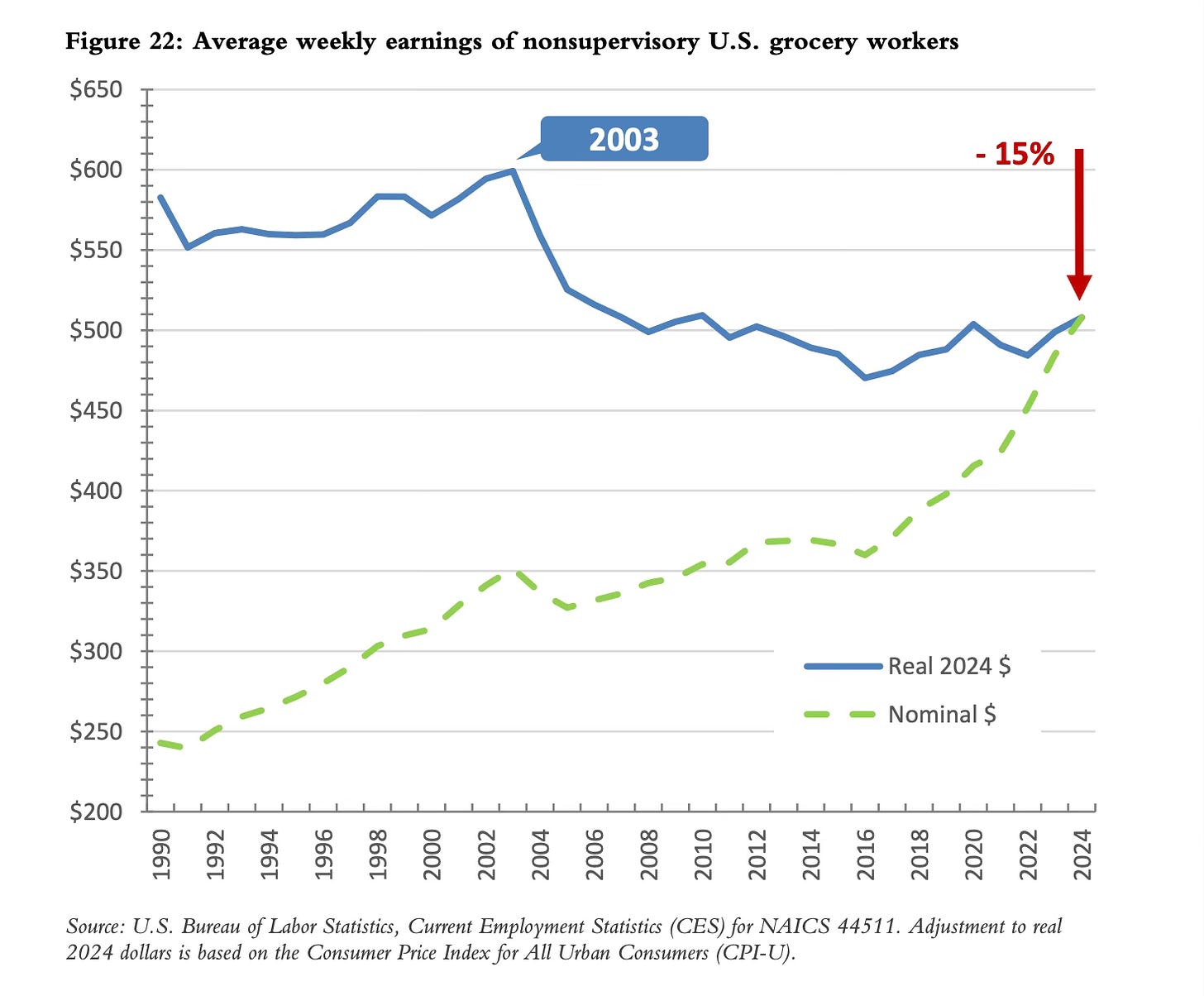

Nonsupervisory employees hours dropped 11 percent, to 28.8 hours. Wages for nonsupervisory grocery workers throughout the United States peaked at $18.55 in 2003 (in 2024 dollars), when the prior union contracts were still in effect. In the aftermath of the Southern California strike and lockout of 2003 and 2004, the average U.S. hourly wage declined to $17.67 by 2024. After taking inflation into account, the actual buying power of hourly wages decreased five percent.

Lower Earnings for Grocery Workers Than Other Industries.

Weekly earnings for U.S. grocery workers dropped 15 percent from 2003 to 2024, when measured in constant dollars. In contrast, the weekly earnings of the total U.S. labor force of production and nonsupervisory workers in other industries increased 15 percent during the same years.

The pay gap between the earnings of grocery workers and their counterparts in all other industries jumped from 32 percent in 2003 to 50 percent in 2024.

The decline in earnings corresponds with a decline in union representation for grocery workers. In 2003, 24 percent of U.S. grocery workers were estimated to be union members. As of 2024, that had dropped to 15 percent.

And an average of five percent of grocery workers employed by Kroger and Albertsons in the three states of California, Colorado and Washington were injured or become ill on the job every year from 2019 through 2023.

Grocery Industry Finances.

While employee real wages and spending power dropped off, Kroger and Albertsons sales and profits skyrocketed.

Kroger’s sales increased 23 percent from 2019 to 2023, and Albertsons’ sales increased 27 percent. The Covid-induced spike in sales of food-at-home generated a decade’s worth of grocery industry growth in just a few years.

Between 2019 and 2024, Kroger’s net income and operating income grew by over 92 percent and 99 percent, respectively. At Albertsons, sales and profit growth was even stronger. Between 2019 and 2024, Albertsons’ net income and operating income grew by over 108 percent and 122 percent, respectively.

Over the past five years, the value of Kroger and Albertsons’ stock has increased more than the overall increase of value in the U.S. stock market.

Despite these high profits, both Kroger and Albertsons have reduced staffing levels.

In 2023, Kroger reported 14.1 percent fewer labor hours per store than in 2019. Albertsons’ labor shortfall was 13 percent of its 2019 staffing level. Both Kroger and Albertsons workers reported missed breaks, departments closing early due to lack of staff, and tasks - such as the regular cleaning and maintenance of equipment - going uncompleted.

Short-term cost-cutting in staffing levels and store maintenance led to less-than-optimal long-term financial outcomes at Kroger and Albertsons. And self-checkout scanners that have been used to reduce labor costs are linked to more theft, more conflict between shoppers and front-end staff, and alienated customers.

Feeding Wall Street.

During the five-year period between 2018 and 2022, Kroger and Albertsons took a combined $15.8 billion in cash out of their businesses and sent it to shareholders in the form of stock dividends and buybacks. As a result, capital expenditures for stores have declined as a share of sales and reduced the capacity of these companies to sustain operations into the future. Ever larger cash payouts to Wall Street shareholders leave less capital available to reinvest in the operations and infrastructure of the grocery business.

Kroger and Albertsons have sought to fund payments to Wall Street by lowering labor costs and underinvesting in infrastructure. These cuts have had negative consequences on these companies’ store operations.

Ecommerce Losses.

The catalyst for ecommerce investments was the acquisition of Whole Foods Markets by Amazon in 2017, which gave rise to investor speculation about the cutting-edge technology and logistical savvy that “the everything store” would unleash upon the traditional grocery store industry.

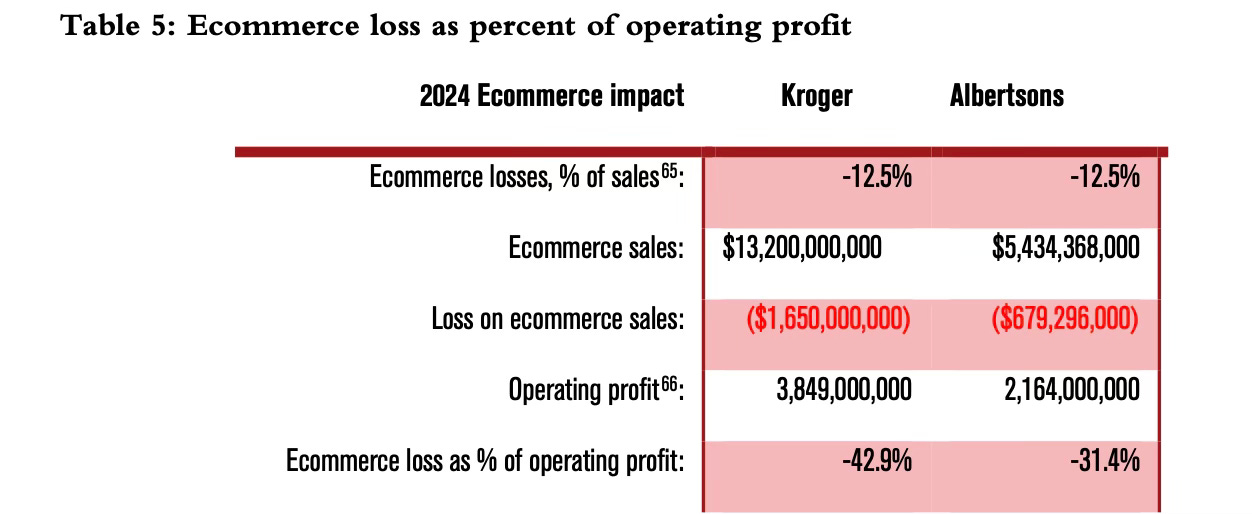

Ecommerce sales of groceries have grown significantly faster than overall grocery sales during the past several years. However, because it is not profitable, increased ecommerce sales require increased subsidies.

Kroger’s profits would have been 43 percent higher without the losses from ecommerce sales, and Albertsons profits would have been 31 percent higher.

Kroger and Albertsons are still attempting to offset the high costs of ecommerce sales by automating ecommerce tasks and by monetizing the customer shopping data collected through loyalty program and ecommerce purchases, using it to generate targeted advertising revenue. However, advertising revenue from selling customer shopping data to food product manufacturers has grown more slowly than the two companies had projected.

Despite the drain on profits, both companies have continued to prioritize ecommerce over investments in the traditional in-store retail environment.

Living Conditions of Grocery Workers.

Nonsupervisory grocery workers experience overcrowded living conditions at a higher rate than workers in other industries. Because of low wages and insufficient incomes to afford adequate homes, too many family members, roommates or even multiple families squeeze into housing units that are too small to accommodate them in order to spread the cost of rent across more people.

Seventeen percent of frontline grocery workers experience overcrowding compared to 13 percent of workers in other industries. Fifty percent of frontline grocery workers are rent burdened compared to 43 percent of workers in other industries.

Economic Outcomes for Local Grocery Workers.

Nonsupervisory grocery store workers living in the counties represented by UFCW Locals 7, 324, 770, and 3000 averaged 28 hours of work per week. The percentage of workers employed on part-time hours is 58 percent greater for nonsupervisory grocery store employees than for the average worker in other industries. Scarce working hours combined with low wages result in working poverty.

The average annual pay for nonsupervisory grocery workers in the study area is $25,659, which is only one-third of the income needed to support a family of four.

The adult partners of grocery workers need to earn 79 percent more than the partner working in a grocery job in order for a four-person family to be able to pay for their basic needs. Grocery workers are unable to be equal partners in meeting the basic needs of their families.

The low earnings of nonsupervisory grocery workers make many of them eligible for taxpayer-supported social safety net programs. Fifteen percent of nonsupervisory grocery workers receive federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits. This is 50 percent more than the 10 share of workers in other industries receiving SNAP.

A higher percentage of nonsupervisory grocery workers receive cash assistance: 2.1 percent, compared to 1.7 percent of workers in other industries. Fifty percent more grocery workers depend upon Medicaid to pay for health care costs than workers in other industries.

Low wages and scant hours of work create hardship for grocery workers and public costs for taxpayers.

A Rising Tide Lifts All Boats: The Broader Economic Impacts of Fair Wages for Grocery Workers.

A $5.50 per hour raise for nonsupervisory grocery workers with year-round employment adds up to a significant annual earnings bump, ranging from $6,400 for Courtesy Clerks to $10,000 for Meat Cutters.

The aggregate increased earnings of $476 million resulting from a $5.50 per hour raise for nonsupervisory grocery workers in the Colorado, Northwest Washington and Southern California study areas will stimulate the creation of the equivalent of 4,906 new local, year-round jobs and $944.6 million in added local sales.

Payroll will increase by $292.9 million for the new jobs created by the additional goods and services purchased by grocery workers, which in turn will create over $526.8 million of new value in the economy.

The additional earnings of nonsupervisory grocery workers will be spent on housing (rent and mortgage payments, 18 percent), health services at hospitals, doctor’s office and clinics (12 percent), banking and insurance services (11 percent), on their own groceries and other retail goods (11 percent), as well as other household expenses.

Other grocery workers who are not covered by UFCW collective bargaining – such as managers and professional specialists – are likely to be indirectly benefited by the $5.50 per hour raise of their coworkers. They will receive an estimated 20.4 percent increase in their salaries as Kroger and Albertsons act to maintain wage parity in their workforces.

The added economic activity generated by a $5.50 hourly raise is projected to produce over $65.2 million in new tax revenue, over a third of which will be added federal tax revenue.

State and local tax revenue are projected to increase by over $49.5 million, with 39 percent coming from additional sales taxes and 34 percent from property taxes.

Public assistance enrollment and outlays are projected to decrease with a $5.50 per hour wage raise, with an overall estimated annual reduction of $65.8 million. This includes federal-funded, locally administered SNAP, Medicaid and cash aid benefits.

-For Full report, see The Economic Roundtable, www.economicrt.org

Errol, Thanks for this great deep dive into the sad state of our nation's grocery workers and essential food workers who provide so much value to their companies. Another sign that the investment class is asleep at the wheel, while the American empire declines.

With the passage of Republican's new Budget Bill it looks like grocery workers are going to take another hit:

"15% of nonsupervisory grocery workers receive federal Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) benefits."

Cutting SNAP benefits is the cowards way to balance the nation's budget.

Thanks again for standing up for our essential grocery workers!