Grocery Update #7: The Sprouts Issue

Sprouts. Not a farmer's market. Still mid.

Discontents: 1. Sprouts Farmers Market: Totally Mid. 2. Product reviews. 3. Tunes.

1. Sprouts Farmers Market.

Let’s get the obvious over with first. Sprouts is not a “farmer’s market”. Farmers are not pulling up at the back dock in their ancient Chevy 2500’s and unloading fresh picked produce. Nope. Sprouts is a grocery store. A decent, adequate grocery store at that, with busy locations across the U.S. That subheading of “farmers market” in their logo lacks the possessive apostrophe that would put Sprouts in the same class of trade as the actual “farmer’s markets” at Union Square, New York City, downtown Milwaukee or Bellaire, Houston. Is it misleading? Maybe. But it’s just a logo. The grocery store is the story here.

This “farmers market” format for grocery stores is a real thing though.

It probably started with Atlanta chain Harry’s, long since assimilated by Whole Foods. Sun Harvest, acquired later by Sprouts, was in this game. Why is that? Implicit in the “farmers market” descriptor is what you see when you stroll into a Sprouts. Full line of site across the store and an open floor plan, led by generous placement of bulk foods, new item promotional displays and fresh produce in center store. Low rise grocery shelving, usually under 6 feet high, with a smaller “center store” packaged foods typically pushed to the back or side of the store. Dairy, meat and deli are usually on one side of the perimeter. Modest health and wellness sections, baked goods, beverage coolers and yet more promotional displays fill in the spaces between, right up until you get to the checkout counters, both staffed and “self’d”.

In a word, Sprouts is “mid”.

Sprouts has captured an odd middle ground in the “natural” and conventional grocery space. Not preachy and high touch like Whole Foods. Not priced to kill like Dollar General or Aldi. Not as convenient or despair inducing like your nearby Kroger using your personal purchase data to predict the best price, time, location and mood swing for your next snack craving. Not much like Walmart, except for a funny connection (stay tuned for that). And not cute and neighborly like your local indie mom and pop that you shop at half out of guilt to keep them in business.

Sprouts is, once again, quite adequate. Extremely ok. Very average. Sprouts is *fine*, said with an exhausted sigh. You can do a whole shopping trip there. They carry just about everything you need and the prices while not the best, are also pretty “mid”. Just good enough. So what keeps folks coming to Sprouts?

Sprouts wasn’t always so perfectly adequate.

Sprouts used to be kind of awful. They leveraged bottom feeder merchandising tendencies to steal market share from higher priced Whole Foods, indies and co-ops. They used to sell cheaper, mostly food service grade produce, very little of it organic. Their meat and deli quality standards were sketchy, even if they dabbled in occasional organic and humanely raised items. Their low priced bulk nuts were last year’s crops and looked like they had gone through a wood chipper before ending up in grubby and poorly rotated bins. Their in-store promotions were aggressive, well executed and very expensive for participating brands. The private label assortment was mostly packer and wholesaler labels that filled value-pricing tiers across dozens of categories. They did little to market emerging food brands. Not anymore.

Ever since former Walmart executive (see, the connection) Jack Sinclair took the helm in 2019, Sprouts has really… sprouted. Sinclair has always been one of the smarter blades in the pack, having led produce at Walmart where he presciently onboarded the Coalition of Immokalee Workers Fair Food Program into their procurement standards. Now Walmart can say they do a better job of eliminating human exploitation in their produce supply chains than Target, Kroger or Albertsons. But alas, like Walmart, Sprouts is still a non-union shop. My former co-workers that have gone to Sprouts after working at Whole Foods or Trader Joe’s usually relay that working there is more of the same, just a little more top-down. You are still expendable, but at least there are plenty of opportunities for advancement.

In the Sinclair era…

Sprouts’ produce selection is now fresher and better quality, but not yet CIW approved. It is also a major draw. Close to half of it is organic and they have clearly delineated sections for shoppers not wanting cross-contamination. Not much of the produce is local or identifiable with specific farms or regions. They still carry the same 3 or 4 mass market berries, 5 or so varieties of apples, maybe 3 types of leafy greens and the industry standard wet rack assortment, amongst piles of shrink wrapped cucumbers, mesh-bagged lemons and greenish avocados signed helpfully with number of days until ripeness. Elsewhere in the perimeter, they are also more clearly merchandising higher-attribute meat and deli items alongside generic, mass-market value options. Sure, they aren’t up to snuff with Natural Grocers or Whole Foods’ stringent quality standards, but they make you think they are.

Sprouts has also stepped in with both feet to the plant-based and meat/dairy analogues’ space, with dozens of offerings across the store. Their private label has become a huge chunk of their sales growth and is a great defensive play against Kroger and Target. They now have enough locations and sales volume to put their own name store brands that can cover most high demand purchase occasions.

Their in-store promotions are still very aggressive, well executed and even more expensive for brands. They still do a reasonably priced, massive bulk foods set. The bins seem cleaner. The bulk nuts, seeds, grains and culinary items are better rotated and a higher grade of quality, on par with Trader Joe’s and Central Market. Plus, they sell just about every kind of snack, candy and sweet treat in bulk. Even day-glo rainbow sour gummy worms. And most surprisingly, they have become THE destination for emerging brands seeking national grocery placement. Their ambitious annual category review schedules, straightforward onboarding/plannogramming process and clear strategic directive to lead on innovation has become a hallmark of their go-to market plan.

Surprisingly, Sprouts has filled the innovation niche that Whole Foods abandoned in 2015.

Whole Foods still launches thousands of new products a year, but is now a slower, more risk-averse follower of food trends. Whole Foods now leans on NIQ data to validate the in-house expertise of its category buyers. In the past, Whole Foods grew sales through first to market, regional-specific merchandising that leveraged national product launches for better promotions and lower costs. Now, while still leading the industry on quality standards and sourcing practices, Whole Foods is hampered by a drawn-out new product review process, a huge national buying team with high turnover, a legacy of regionalized, store-specific plannograms that must be updated by the dozens to do any round of store resets, and a focus on P.R. that tends to outpace their actual, in-store retail execution. Just so much P.R. Such strategies were implemented by the phalanx of former Target and Walmart executives that have led Whole Foods merchandising since 2015. Alongside ever-increasing supplier fees and a young CEO with more roots in management consulting than retail operations, these are the hallmarks of the post-Amazon Whole Foods era.

Sprouts instead trumpets its innovation through well-curated displays in stores. New items carry risks for retailers, both through shrink and cannibalization of existing sales, so Sprouts extracts huge revenues through slotting/store placement and promotional fees from these suppliers. Like Whole Foods, their new item attrition rates cycle well above 50% annually. Do they make more money off of the fees than actual new items sales? That is worthy of debate. But while it is now more rare for new suppliers to build a successful business through Whole Foods than in the highly mythologized success stories like Epic Bar, Siete Foods or Justin’s Nut Butter, emerging brands are more excited to take a gamble at success through the Sprouts meat grinder than the post-Amazon Whole Foods politburo.

And Whole Foods is contractually wed to wholesaler United Natural Foods (UNFI) for the time being. Their volume dependent mark-up gets lower every year, meaning more of UNFI’s fixed costs pile onto the shoulders of rent-burdened, stressed-out suppliers through deductions, upcharges, billbacks and other fees. Sprouts uses independent, employee-owned KeHe as a primary wholesaler, but in much the same way- a parallel wholesale model. This enables Sprouts to have a similar wholesale mark-up as Whole Foods while also calling the shots in many of the KeHe distribution centers. Their volume enables them to be the primary retail account for Kehe, like UNFI is for Whole Foods, so category decisions don’t get subsumed by some other retailers’ product assortment priorities.

Like their wholesaler programs, Sprouts’ promotional and new product introduction fees are expensive to suppliers, but they get executed in stores. Suppliers are also not paying the 3% merchandising fee that Whole Foods charges. This wildly unpopular toll subsidizes outsourced merchandising services that keep store operating costs down. It is an original and innovative kickback scheme conceived by the ex-Target crew and it generates close to $100 million in annual revenue, 50% of which reportedly goes to the Amazon division’s bottom line. The extraction never stops.

Sprouts investments and insights into new product innovation has also informed their rapidly growing private label program, which is at least on par with Whole Foods or Kroger’s Simple Truth in assortment and quality, and a step beyond what most other grocers are doing. It is no coincidence that so much of the new Sprouts exclusive products assortment resembles their trendy new items that come and go so quickly, both in style and content. That is called having a good exclusive brands strategy. Yes, it leans a little too close to the product development plagiarism that Trader Joe’s has become so effective at. American capitalism, at its best, is still a fun-loving criminal enterprise. Drive it like you stole it.

These strategies keep Sprouts a-sproutin’.

Sprouts has shrugged their shoulders at the Kroger-Albertson’s merger hullabaloo, maybe because their unique positioning also makes them a tasty merger/acquisition target. Their sales have increased by over $1 billion since 2019, to over $6.8 billion in 2023. They keep hitting high single digit sales growth and mid-single digit comparative store sales growth targets, better than the overall grocery sector. They are non-plussed by Whole Foods’ Amazon-era price investments. Their middle of the road pricing strategy keeps them on par with key value items (KVI) while avoiding much of the non-KVI price gouging that Whole Foods’ high standards and high margins demands.

Sprouts is a major threat to natural products co-ops and locally owned, independent grocers, but mostly if these retailers don’t have good private label, promotions and new product introduction programs. It is not impossible to stay insulated from Sprout’s. Cooperative purchasing resources from groups like Wakefern, INFRA and NCG can be plenty effective. But Sprouts executes their merchandising very well and their primary Kehe relationship helps maintain inventory levels even on busy days. This, while seemingly obvious, has become much harder in the post-covid world and can’t be said of Whole Foods or Target. Unlike Trader Joe’s, Sprouts can be a complete shop for a family. Unlike Kroger, they are a small enough format that a shopping excursion doesn’t take half the afternoon, plus you don’t feel like the McMullen gang knows everything about your most intimate personal consumption habits.

And Sprouts doesn’t have the charm of Mom’s Organic Market, the low-priced gravitational pull of Aldi or Walmart or the high standards and oddball quirks of Natural Grocers. It is still doing that “farmers market” shtick. Sprouts, by tightening up their go-to market strategies, is full of optimism and momentum and still remains, happily, stubbornly “mid”.

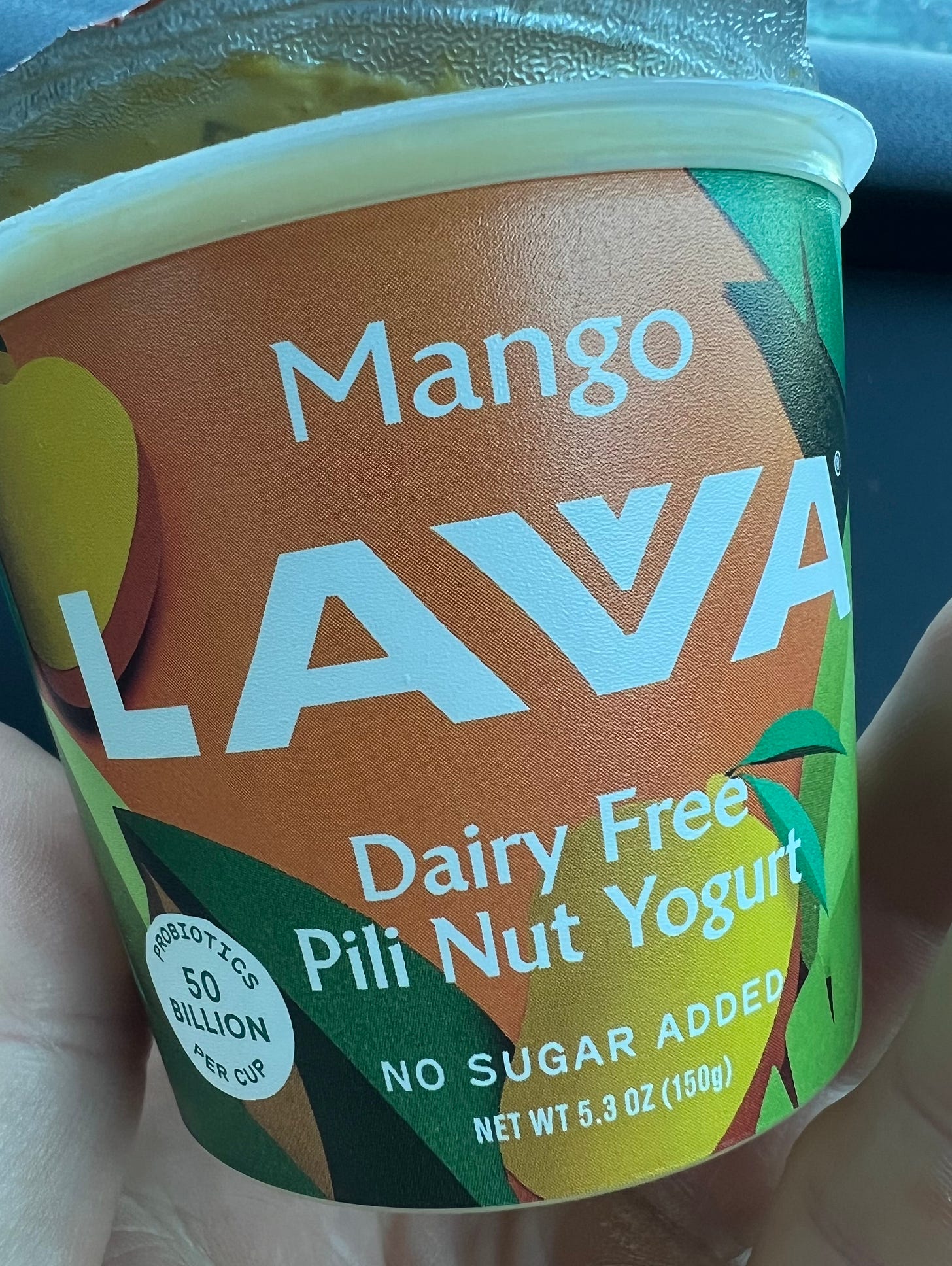

2. Product review: Lavva Pili Nut Yogurt.

Elizabeth Fisher is a grocery industry icon. She would never say that herself, so we can say it for her. She was an early sales leader of the iconic Robert’s American Gourmet before the cheesy poofs and vegan Pirates Booty ended up in every discounter, club store and bodega. She also ran sales for KeVita before it was chugged by a Pepsico acquisition.

Elizabeth is a champion too. Her personal experiences have motivated her to research, source, formulate and market Lavva, a best-in-class, plant-based yogurt, made with the high fat pili nut. It is perfect for eaters who have glycemic or metabolic issues, or who are trying to stay ketogenic. It is also quite tasty for the rest of us. While Lavva is a bit harder to find since Whole Foods cut back its national placement, it is stocked in plenty of East Coast grocery stores. Big appreciations to Elizabeth for moving this industry forward with healthy, better for you products.

3. Tunes.

After that little Sprouts excursion, this one is too obvious. But it never gets old.

peace.