Grocery Update #64: The New Spice Traders.

Burlap & Barrel and Diaspora Co. Sound Off On Tariffs, Trade Wars and Building Ethical, Transparent Supply Chains.

Discontents: 1. Four Questions With Diaspora Co. 2. Interview: The Burlap & Barrel Model of Trade.

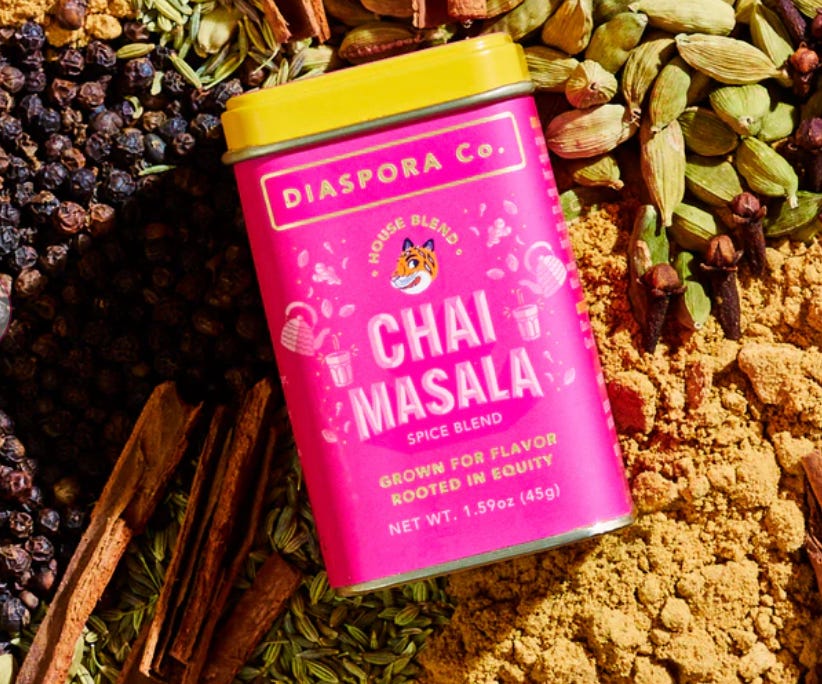

1. Four Questions With Sana Javeri Kadri Of Diaspora Co.

1. What inspired you to launch Diaspora Co.?

I wanted to build a better spice trade –– one that is fair, flavorful, and transparently sourced. As a young woman born and raised in postcolonial Mumbai, working at the intersection of food and culture, I was slowly discovering that since the colonial conquest some 400 years ago, not much about the system had changed. Farmers made no money, spices changed hands upwards of 10 times before reaching the consumer, and the final spice on your shelf was usually an old, dusty shadow of what it once was.

2. How does the brand stand out from other seasoning brands?

At the end of the day, flavor is what makes Diaspora Co. stand apart from the many other spice brands on the shelf. We work with farmers to grow for flavor, and we do this a number of ways: by building deep relationships with our farm partners, through lab testing and specific growing methods, harvesting for peak flavor, rigorous quality testing, and iterative blend development.

3. How will increased tariffs impact the supply chain?

In our nearly 8 years in business, we’ve never once lowered the prices that we pay our farm partners, only raised them. We continue to pay them an average of 4x ABOVE the commodity price, what we believe is a truly equitable wage for their beautiful spices. To date, we’ve paid over $2.5 million dollars directly to these small, regenerative farms. So, despite the tariffs, we are committed to not lowering prices on any of our farm partners. Doing so would be antithetical to our mission and values.

We also know that every single one of us is feeling the panic and pinch of the rising costs on our grocery bills and with each passing paycheck. So at this time, we won’t be raising prices for you, our community, either. Most likely, this will mean that we won’t break even this year. We’re an incredibly lean, nimble and frankly wonderful team spread across India and the USA, and each team had many big and bright plans for this year that we’re all putting on pause until we know more.

4. What is your vision for the food system?

A food system that is equitable, flavourful and rooted in culture.

Editor’s note: And a word on “curry'“, from Asha Loupy and the Diaspora Co. newsletter (subscribe here!):

“Curry” powder has long been one of the most controversial spice blends. This seasoning, often labeled “Madras Curry Powder”—Madras, now Chennai, was one of the major trading outposts for the East India Company—in the spice aisle, isn’t actually South Asian at all. It’s a product of—you guessed it!—British colonialism, whose original intent was the domination of the spice trade. As the arms of colonialism spread, the British sought to reduce the breadth of South Asia’s cuisine into one powder, and so “curry”—said to be derived from the words kari in Tamil and karil in Kannada and Malayalam—became the imperialist catch-all for a symphony of regional dishes whose only major common thread was their sauciness.

“The paths traveled by “curry” powder are long and many, with versions making their way to Trinidad, Guyana, America and beyond. If you haven’t read Julia Fine’s Whetstone South Asia article “From Delhi to Durban: The Many Homes of Madras Curry Powder,” it’s an essential, deeper dive into this blend (there’s only so much space we have in one newsletter, after all). And, luckily, over the past few decades, there's been a growing number of chefs, food writers, and companies who are highlighting regional South Asian cooking, unweaving the ties of colonialism, and focusing on spices and blends that are specific to states, cities, and even farms.”

2. The Burlap & Barrel Model of Trade.

Interview with Ethan Frisch and Ori Zohar, from The Checkout Podcast. Transcript abridged for clarity and brevity.

Business Model.

Errol: What is Burlap & Barrel?

We are a spice company, a single origin spice company and a social enterprise. We work with small farms in 30 plus countries around the world, mostly with producers who have never exported before, but are growing something really special that we think has value to the US market that that farmer hasn't been able to find elsewhere, through the commodity market or locally, and so we set them up to export. We do all the logistics and paperwork and all the work of bringing their product into the US for the first time, and then we pack it and sell it here. We sell it online, through our website. We also sell through retailers, through fair and food service and bulk programs too.

We've been doing this for almost 10 years. And we have everything from, like, way, way better versions of your basics, like our cinnamon is insanely sweet, a little spicy from Vietnam. It's really beautiful. But we also have really rare and unique varietals, like wild mesquite fruit powder that really is somewhere between vanilla and cacao. We have really cool dulse flakes from Canada. We bring in really, really special, unique spices from all over the world. And I think with us, you can really stretch out your definition of what spices really mean and find all kinds of awesome new ingredients.

Errol: What's your sourcing and supplier philosophy?

It's a philosophy that has certainly evolved over the almost 10 years we've been doing this as we've learned a lot and gotten better. Neither one of us had any experience in the spice industry or really in CPG food at all before starting this company. I would say some key elements of our sourcing philosophy, one is that the relationship is really important. We get to know the individuals on the other side of the supply chain. We visit farms. We understand their agricultural practices. We're in regular communication.

Another key part of our sourcing philosophy is quality, and by that, you know, you say the word quality in food, it can mean all kinds of different things, but for us, it means it means flavor, it means intensity of flavor, that the spice really speaks for itself. And so even if you don't really know or care that much about our social enterprise mission, or know why we're doing this, the cinnamon is still the best cinnamon you've ever tasted. And that quality, you know, that really what I find convinces the customer. So that's really important in sourcing.

And then, the third thing we look for is an entrepreneurial mindset from our supplier, you know, a farmer who has seen the same problem that we have seen in the supply chain, that they don't have access to the higher value market, and that customers in those markets don't have access to their good products. Often, when we show up on a farm for the first time, or when, you know, when things go well, we show up on a farm for the first time, we say, here's our idea, and the farmer goes, well, what the heck took you so long? You know, just having found an import partner on the other side, so a farmer who's willing to take on the additional work of exporting that often involves sorting, cleaning, packing, trucking things around, coordinating with logistics companies. Not really the bread and butter of farming, necessarily, but when a farmer or a family member of a farmer or somebody in their immediate community can help them pull that off, it's a huge unlock for them to be able to export their products and keep that extra margin that might otherwise have gone to an intermediary. So that's the third element, an entrepreneurial partner who's enthusiastic to sort of take on this challenge with

Errol: How does it differ from normal spice and seasoning supply chains and sourcing that you see in most grocery stores?

The spice trade is really an example of consolidation, where you have a lot of small producers in Vietnam, in India, and, you know, all over the world, really, who are selling into a commodity supply chain. So an individual farmer might sell to a local broker, a buyer that might be somebody with a little warehouse in the local shop, or a truck driver who's going farm to farm and buying up harvests throughout the season. Sometimes it's relationship based where they sell to the same people every year. Sometimes it's kind of spot buying. Or they'll sell to whoever gives them the best price, right on the spot, and then that intermediary is then, in turn, doing exactly the same thing, passing it along to somebody who's a little bit bigger than them, a bigger warehouse, a bigger truck and so spices can change hands a dozen times before they've left the country of origin.

The downside of that is that if a farmer, if an individual farmer, is doing something special, it all gets lost, because all of those peppercorns are being mixed together to create an unhappy medium, a medium low quality product that will satisfy the customer requirements, but isn't really doing anybody any favors in terms of quality or certainly not traceability. And then essentially have the same process on the other side. Eventually it makes its way to a big exporter, and then it comes into a big importer, who's then breaking it down into smaller shipments and selling it to smaller companies, who are in turn selling it to smaller companies. And at some point along the way, it gets packed. As you can imagine, that process can take a very long time.

Some of that is just because of the logistics. It takes a while for prices to move around the world, but often the delays are financially motivated, waiting for prices to go up or go down, stockpiling inventory when it's cheap. That's happening, from big companies. But it's also happening at the farm level, where a farmer will say, Okay, well, the going price this year it is low, so I'm going to sit on my harvest until the off season to try to get a higher price. You know, there's a lot of gaming that happens at all levels, and none of it is really to the advantage of the consumer or the end user of the product. It's all in service of price and not in service of flavor or quality. And so that's what we try to turn on its head and really focus on flavor and quality. And that means paying farmers a lot more often, paying that money long before they harvest. We put big deposits down months, or in some case, a year, before the spice is going to arrive in our warehouse.

But it's important to make sure that they have all the equipment, the inputs, the staffing, everything they need to do a great job of harvesting a premium product. And then, yeah, we bring it in as quickly as possible. So often we're contract farming, they're producing for us, and then it gets shipped out essentially immediately, as soon as it's harvested and dried. And so we could have something in our warehouse within weeks of harvest and available on our site shortly after that. So that's kind of the difference. One is the investment that we make at origin. One is the speed at which we move. And third is the particular products you know, focusing on products that have a terroir, that come from somewhere significant, that you know, whether it's the skill of the farmer or a certain technique that they use, or the soil quality or the climate that really contribute to a unique product.

And we've built our business in a fundamentally different way from what you're seeing on the grocery store aisle, like you're seeing these alphabetized, commoditized spices. What kind of cinnamon is it? There are different varieties. Where did it come from? All this stuff. And so it was really important for us to be a social enterprise and to be a single origin Spice Company. We've known single origin from coffee and tea and chocolate. It's the reason we go to farmers markets. It's the reason we go to our butcher and cheese monger. It's our connection back to who made these things and ensures that there's a clear and transparent supply chain behind it.

So the same way that you have that kind of fresh apple that was picked that morning, you know, at the farmers market, versus the one that's been in cold storage for 6 to 12 months, that's exactly what we're doing in the spice world, and that's why we think about ourselves as kind of a third wave Spice Company, where the first wave is big commodity importers. Everything is just under the category of what it is. Cinnamon is cinnamon is cinnamon. Doesn't matter. No further information. The second wave were spice companies here domestically that we're buying from better importers, and third wave is what we've been doing around single origin, where we are the importer.

So it's a fundamentally different business. We're not working with just like co-mans that are pulling in inventory from somebody else, from somebody else, from somebody else. We're actually building all these supply chains directly ourselves that you can mention, big down payments and all that. And so we have that kind of traceability. It's a wild business to build as a bootstrap social enterprise because you have to really put so much more money into supply chains and into inventory and into all that stuff, but the payoff is huge in terms of flavor, in terms of quality, and in terms of when the supply chains in the world are going crazy, we still have these really strong relationships with our partner farmers, and are still able to get the same quality of ingredients consistently and working directly with them to bring it in. So it's a really fundamentally different business than all the other ones that you'll find in your grocery store shelf.

Errol: What quality assurance and food safety measures do you take? Spices can be very dirty.

Great question, thanks for asking about this! We take food safety very seriously - I manage our food safety program personally and have final say on all food safety related decisions. For the past few years, we've taken a supply chain-oriented approach, looking first for ways to reduce the risk of contamination on the farm rather than relying on sterilization in the US, which is what most other spice companies do. The vast majority of our spices (95%+) do not need to be sterilized because of the careful prevention work done by our partner farmers at origin. We test every shipment at least twice (at origin and upon arrival in the US) and we sterilize when necessary using a proprietary (to our vendor) steam and heat process that retains as much flavor as possible. We don't use ETO anymore (although we have in the past for certain products) and we have never used irradiation. We also have a rigorous metal detection step before packing (in the US) and our spices are packed in small batches with close oversight by a team of professionals (at our copacker) to detect any potential foreign materials. For certain spices, we also test for lead and other heavy metals, and we abide by the NY State standards, which is the most rigorous in the country (and which I have been involved in lobbying in support of the new strict limits.)

Errol: Do you pay living wages to your employees?

Yes. I'm not sure what the technical definition of a living wage is in all the different areas where our employees and contractors live, but we pay very well, with regular raises, performance-based bonuses and plenty of perks including unlimited free spices. We currently have 21 core team members, of whom 9 are salaried employees and 12 are hourly contractors and we're fully remote, with team members in a half dozen different states. We have very high levels of employee retention - no one has ever quit or been fired in the lifetime of our company. We take a flexible approach to work-life balance, encouraging our team members to build their work schedules around their other life activities and commitments, rather than the other way around. Many of our employees are from non-traditional profiles - military spouses, retirees, entrepreneurs, etc - who might not be formally employed otherwise. Our customer service team, for example, is staffed by former customers, three of whom are former medical and mental health professionals. Ori and I are very experienced team managers, with at least a couple of decades of diverse management experience between us, and we take our management responsibilities very seriously.

Tariffs.

Errol: So let's break it down first, as an importer, explain what a tariff is and how that works relative to your supply chain.

A tariff is a tax that's imposed on us as the importer, on a percentage of the value of the product that we're bringing in. So we bring in a shipment of cinnamon worth $1,000 then a 10% tariff, we would get charged 100 bucks on that shipment. This idea that the tariff is paid for by somebody else, by somebody in another country or another government, it's just not accurate. I mean, we're the ones who are going to get the bill. We pay US Customs. The US government sends us a bill that we have to pay. And I think a lot of the idea behind tariffs is like, let's, let's protect American industries, and let's give companies an incentive to switch their suppliers to domestic ones.

The problem with the world of spices is that so many spices have no business growing in America. Their tropical plants. They grow well, and so many other places where they've been growing for centuries, for millennia. And so really, what we're what we're seeing, is that we're going to have to pay tariffs on this really incredible Vietnamese cinnamon, a royal cinnamon that is so special for what it comes in there's no domestic cinnamon in America.

And in fact, I think that the whole point of spices is to help you travel around the world and cook from cuisines and from cultures, and tap into these shared human experiences of travel and going around the world. It just ends up really being a punitive tax on businesses like ours, where we're an American employer, we support the Postal Service and send a lot of packages by mail. All of our team is domestic, including our customer support. We work so, so hard to build this sustainable American business and employer and all that, and now we're kind of being faced with the risk of huge, huge taxes on our business because of the way that that we work to source spices from places abroad that don't grow in America.

Errol: What will that do to your business model if the Trump administration moves forward with higher tariffs?

It obviously has an impact on our bottom line, an added cost is a cost that has to be covered somehow. In our case, we're not going to raise prices and we're not going to cut payments to the supplier. So that's going to come out of our bottom line. That means, in a practical sense, that we're going to do a lot less innovation. You know, we crank out 50 new products every year, we're going to do a lot less. You know, specifically, we've worked on an advent calendar project that's not going to go ahead, lots of stuff along those lines, because the unpredictability of sourcing just makes them too risky with that added cost attached to them. But then the unpredictability element is a whole additional level of eroding trust in the American economy, eroding trust that farmers have, that our suppliers have in the American economy. We've grown with our partner, farmers, with the understanding that we had a big and growing market for their product here. And if that's not the case, either because the products are being tariffed or the economy is collapsing, or whatever it might be. I think we still have not yet seen all of the effects of this, this tariff action on the supply chains from how are suppliers around the world are going to see the US differently as a result of this.

When we walk into the room or into the field to meet our partner farmers all over, our identity as American precedes us. And so in the past, when we walked in, they said, Great, we want to sell to America. It's a big market. It's a reliable partner, and that really helps us, because so many of these these relationships are trust based. We don't have deep contracts with rural star anise farmers in Northern Vietnam. It doesn't work that way. So really, it's about trust and reliability. And it feels like now, in the past, being American has been kind of tailwinds of saying, oh my god, the Americans are here. There's an opportunity to grow our business, to gain entry into this market that's wealthy, that has a lot of people that are cooking and buying, and it's this massive market of 300 million plus people. We're worried that now, as we step back into the world, all of a sudden, what's that reputation going to mean to be an American? And is that going to be more headwinds than tailwinds to say, no, no, we're not like what you've read in the news.

We're not like the people that that you've heard that are changing their minds and having huge costs and changing their decisions on business. And so I think this underestimates how much of our business is built on these trusted relationships, and how much we end up becoming ambassadors to America, to these farmers that we're working with. And then on the flip side of that is domestically, we're working really hard to plan our holidays right now, in November and December, we're placing big orders for these annual harvest of spices that are really going to come and hit in the holidays this year.

We have no idea what the state of the American economy is going to be. We have no idea what people's appetite is going to be for spices, for cooking, for spending, in general. And so this just makes it a really wild and unpredictable world to live in, and if these tariffs are a negotiation tactic, as some people claim they are, we don't know, but there's a lot of collateral damage here, and a lot of businesses are scrambling. And I think in particular, small businesses are scrambling because we don't have this redundancy.

We don't have forecasting teams. We don't have giant relationships with banks and finance and all that stuff. And so we both can't ignore these tariffs because they come out of the White House, but we also can't take it seriously because tomorrow it might all be gone. And so this is where we're really in in an unpredictable situation, and that's why we try to show up in the world with talking to our customers, letting them know what's going on, asking them to buy spices right now, since all the spices in our warehouse are kind of in their pre-tariff costs, you know, so this is a good time to pick up spices.

But we also made a really, really non-negotiable commitment not to ask our partner farmers to cover any of these costs, and to agree that we're not going to increase cost on our customers, either. We said we're going to slow down innovation. Maybe we'll have to save a little bit of money on our packaging. Maybe we're going to have to slow down shipping a little bit. We don't know what yet. We'll see how bad it gets. But right now, we don't want to short change the quality of the product that we have here.

Our business is insulated because we're importing a raw material, a bulk spice. Most of the value added processing, at least of single spices, is done here. So we package them here. So ultimately, the cost of the spice itself is a small part of all of the costs that go into assembling the jar. That's one element of it, and the other is that we're direct to consumer, so we have margins, or significantly direct to consumer. So we have margins to absorb those, those added costs, so that they're not excess.

But for other companies that are dependent on retail distribution or margins are much slimmer, where they have much less control or harder to access their customers directly, I would say those kinds of businesses are much more vulnerable. Because of the kind of business that we wound up running, shaped by the pandemic, and kind of cultural and economic forces, we're insulated. We import from 30 countries, almost 100 plus spices in the lineup.

So we're trying to watch it. But we're trying to be really crafty about separating out the cost of the raw material from the value added services, all this other stuff, and because we're not locked into these big national distribution relationships, and we can have a lot more flexibility and fun with what we're bringing in, and we're showing customers we can do so much more interesting stuff.

And by the way, we do source a lot of spices from the US, including chilies from California, including salt from a father daughter team in upstate New York. And so we are working with a lot of domestic producers of spices. We have wild ramps that are dry. And this is going to weigh on us, on our decisions and how we work, but this in particular, because how we're built, and we have these directions with partner farmers, and there isn't this waterfall level of cost increases, because normally the origin that's exporting is going to have a cost increase in the importer, and then the distributor, and then this and that. And everybody has to take their bite, those like small ripples of cost increases end up becoming dollars at the register. Because we have this direct relationship, we're not gonna have to bear the cost in that same way.

Trade.

Errol: What's your vision for what trade could and should look like?

We had seen the problems with systemic capitalism from different angles and the spice trade, we like to joke it's the second oldest profession, it goes all the way back 1000s and 1000s of years in human history. People have been trading spices, transporting delicious things that grow in one place to another place. You know, even before recorded history, there's evidence of that happening. Ancient Egypt was importing peppercorns from India.

So we see ourselves as stewards of that legacy, an older style of international trade and sourcing that's not capitalist in the sense that it's not focused on capital and the power of capital, but is focused on relationships and an alignment on product quality, farmers who are really proud to grow a high quality product, who have put decades or generations of expertise, learning to do it in a particular way and developing a certain technique. More than money, they care about having their product be appreciated because they have put all that work and their own care and appreciation into it. And that's how we show up. I mean, that's what we're looking for, too, is a product in need of appreciation, and then we have this amazing base of customers that has grown steadily over time.

We had a huge spike through COVID. We were mostly a restaurant supply company before COVID, and the direct to consumer business grew through the second half of 2020, really like 1,000% from 2019 to 2020, in our direct to consumer business, we found this community of home cooks in the US who really care about quality and have a core set of shared values around the planet, around a certain style of agriculture that yields a superior quality product. And so that's how we've conceived of this, this system of trade, going back to an earlier style of the spice trade, where it really was people who knew each other and cared about the product, working together for everybody's benefit.

What if we wanted to make a domestic spice industry here? We would spend a ton of money building greenhouses to replicate the correct environments, we would spend decades cultivating the trees. And our cinnamon comes from trees that are over 15 years old. Like, we can do it, but it will be inefficient, expensive, and take about a century. And so, like, in terms of trade, what we're doing here is we're bringing spices from where they grow the best. We went to Grenada. Do you understand how nutmeg trees grow there? They can't stop them from growing. It works so well. It's this really beautiful thing that that ends up giving the absolute best, best versions of these spices.

And we've now gone and built a network around farmers and think of them as individual entrepreneurs that work with us, where they have their own vertically integrated kind of growth methods, where they're growing the spices, cleaning, drying, grinding, preparing for export. They're doing it really, really well from the way they're growing the spices, all the way together and ready for export. And as a result of working with us, they're also making a lot more money from it. And then we bring them into the US and then we do all the value added domestically here. So I think it's really easy to kind of write this off as jobs going elsewhere, but these are jobs that would be, at the very best, fundamentally inefficient and way more expensive in the US. And on the flip side, we are a US employer. Our entire team is domestic.

And so this is where we feel like, with this way of thinking in this policy, it feels like it's really punishing the kind of A-plus students that are building domestic businesses and employing here in order to bring things into the US that grow inefficiently. Or what's actually happening right now is that there is no domestic market, so it's just purely a tax on our business. So the philosophy of trade is all around who does things the best, especially around this agricultural philosophy, and we all benefit from low prices, higher quality, and we're still a 100% US employer in this whole process.

So that's where this is leaving us scratching our heads and having to reach out to our customers and ask them to support us and to support all the other small businesses they really like, because in this turbulent time where we don't know what's going to happen, where we may need to bear really high costs, and where we're going to try to find different ways to rein in our business cost in order to kind of be able to absorb these, that's where our customers come in, and it's absolutely wild that we have to ask our customers for help from us government policy in order to continue growing in this climate. So this is where we're all scratching our heads, but we are trying to make the most of it. And our customers have really shown up, and it's really nice.

And this is our ask for people too. Is if you have businesses that you love and products that you love, and small entrepreneurs and all of that, this is the right time to step up, because your dollars really matter, and choosing the specialty thing over the mass market thing really, really has a big, big role in shaping the world in this moment.

The tariffs are insult to injury at this point. The bigger problem is that the economy is collapsing, and the government seems to be in on it, so that the tariffs certainly will add some specific costs. But I think our bigger challenge is the unpredictability of the economy that we see stretched out ahead of us. What's that going to mean for supply chains? What's it going to mean for production? What's it going to mean for distribution, for sales? You know, what do we do if our customers can't afford spices, or as many spices? That's why our commitment to not raising our prices has been so keen. You know, accessibility is really key. We did some of the math quickly last week when the tariff announcement came out and saw that we would likely lose more business by raising our prices and slowing down sales as a result, of course, then by keeping our prices steady and taking a taking a smaller cut.

And if we're going to be in an inflationary environment where prices are increasing, and we saw this in the pandemic too, people are going to lean on things like spices to cook, to cook better food, they may be cutting back their travel. They may be cutting back their eating out at restaurants. And so what we're trying to do is we're here to make you feel like you're eating an absolute five star meal at a few cents per serving. So I think that when times get a little tight and people tightening their belts, we don't want to also be increasing prices. In fact, we want to try to be there as a little bit of a place where you can still connect with friends and eat well, and just come out from the world a little bit and kind of still live your wonderful food life while saving money.

What we do now is more important than ever to bend capitalism into the right direction, because it seems like the current administration is just supporting rampant wild, wild capitalism.

And I think that that's dangerous, and so we really want to prove that we can be a social enterprise, a for profit, business support, small holder, farmers, give home cooks in America a really good value like, we're trying to check all the boxes and show how all this really can come together, that everybody along the supply chain ends up getting their fair share and ends up getting a really good experience. So that's our overarching philosophy behind this.

peace.

So interesting -Very well thought out and written.

Very interesting.