Grocery Update #41: Farmworkers In The Supply Chain

Also: Busting Organic Food Myths. And Kimchi Of The Week.

Discontents: 1. Mythbusting Organic Foods. 2. Farmworker Testimonials: Life In The Supply Chain. 3. Kimchi Of The Week. 4. Seen In The Wild. 5. Tunes.

1. Busting Myths About Organic Foods.

There is a lot of mythology and misinformation around organic foods. The organic news lately is mostly good. And the USDA Organic seal, despite some flaws, continues to be the leading light of the “better for you” food movement.

Organic product sales in the U.S. approached $70 billion in 2023 and will have grown more in 2024. Organic produce led the way, with $20.5 billion in sales. Organic produce now accounts for more than 15 percent of total U.S. fruit and vegetable sales. And organic groceries, beverages and dairy products saw decent growth and stable market share in an industry beset by inflation and stagnation. Organic is 5% of grocery sales and just 1% of acreage in the U.S., so there is tremendous opportunity for domestic farms to bridge the supply and demand gap, and there is a lot more USDA assistance out there for such transitions.

(The Checkout Grocery Update loves potato chips and really loves pickles. We are proudly sponsored by The Specialty Food Association.)

Over 70% of consumers trust the organic seal and 90% are familiar with it. Organic production methods vibe with many consumers who are looking for sustainability, transparency and climate friendly products. They are rejecting GMOs, hormones and antibiotics, and carcinogenic herbicides and pesticides, despite the best efforts of agribusiness and food tech marketers. They want food that supports a stable climate and increases biodiversity. Organic delivers on all counts.

While organic products cost more, most consumers think the price gap is warranted, especially considering that organic supply chains externalize vastly lower costs than conventional products. The retail price gap is also narrowing, due to climate impacts, but also due to availability and improved efficiency in growing practices.

There is still plenty of work for the organic sector to do.

There is little farmworker input on organic standards and zero farmworker representation on the National Organic Standards Board. Farmworkers stand to gain the most from growing foods that won’t poison them, but have been historically marginalized by the organic sector (with exceptions such as ALBA). So while organic farms can pay well and treat workers better, they are not required to.

There is a defensiveness from the organic sector when it comes to overlapping certifications such as “regenerative”. Sometimes this defensiveness is justifiable: a recent report on “regenerative” brands barely mentions that many of the most successful products they profile are also organic, and are probably selling so well due to their organic labels, not just vague “regenerative” claims.

The organic industry should clarify its relationship with this growing horde of regenerative frameworks. Are some potentially relevant to transitioning to organic and beyond, such as Regenified? Or are they filled with loopholes that promote basic crop rotation while still spraying glyphosate, in order to capture some premium market share? There is also room to learn from the efforts of regenerative organic producers certified through the Regenerative Organic Alliance, which is growing tremendously.

Organic could also partner better with Non-GMO Project (Disclosure: I am a longtime board member). Non-GMO Project provides a line in the sand against GMO contamination of food supply chains. That is a huge boon to organic foods. And products with both seals sell better, going back to my Whole Foods days and even until now. Products with both USDA Organic and Non-GMO Project Verified saw sales of $7.04 billion in 2023, growing 13.7% — more than USDA Organic or Non-GMO Project Verified alone.

On the other hand, many of the criticisms leveled at certain organic certifiers, such as by Real Organic Project, should be taken more seriously. There is a quality and consistency issue in private label dairy and eggs, particularly whether producers utilize so-called “organic CAFOs”, that are essentially factory farms. As an example there is a visible difference in product quality between various private label organic butters. Another example would be hydroponic products that are not grown in soil. Such products do not have their own labeling rubric. Many organic berries are now hydroponically grown. And the organic seal also faces a threat from synthetic biology products finding their way into supply chains. To paraphrase abolitionist Wendell Phillips, eternal vigilance is the price of organic liberty.

But in the grand scheme of the food system, these are reformable problems. Organic is still the gold standard for consumers. Not perfect, but a great starting point.

Our friends at Foodprint put together an awesome analysis that disentangles some of the confusion around the USDA Organic certification. They also have a great explainer on organic foods that goes even deeper.

Here are the highlights:

Myth 1: Organic uses just as many pesticides as conventional agriculture.

FACT: ORGANIC DOES ALLOW NATURAL PESTICIDES (AND A FEW SYNTHETICS) — BUT THEIR USE IS VERY LIMITED AND NOWHERE NEAR THAT OF CONVENTIONAL AGRICULTURE.

Myth 2: Organic is actually worse for the environment.

FACT: ORGANIC AGRICULTURE HAS A LARGER LAND FOOTPRINT THAN CONVENTIONAL, BUT IT IS MUCH BETTER ON ALMOST EVERY OTHER ENVIRONMENTAL METRIC.

Myth 3: There are no health advantages to choosing organic.

FACT: PERSONAL HEALTH ASIDE, CHOOSING ORGANIC PROTECTS THE HEALTH OF FARMWORKERS AND MITIGATES SOME SERIOUS PUBLIC HEALTH RISKS.

Myth 4: Organic is just an excuse to charge more.

FACT: UNLIKE MANY MARKETING CLAIMS MADE ABOUT FOOD, USDA ORGANIC HAS SPECIFIC RULES AND A STRINGENT VERIFICATION PROCESS.

2. Life In The Supply Chain: Farmworker Testimonials.

(Publisher’s note/Trigger warning: This section contains testimonies of sexual violence experienced by farmworkers).

There is no food without farmworkers. The most essential labor in food supply chains rarely gets its due, and more often is subject to working conditions that many of us couldn’t handle for a day. One of the priorities of The Checkout Grocery Update is to platform such folks to speak for themselves, what they experience and how they want to change their circumstances.

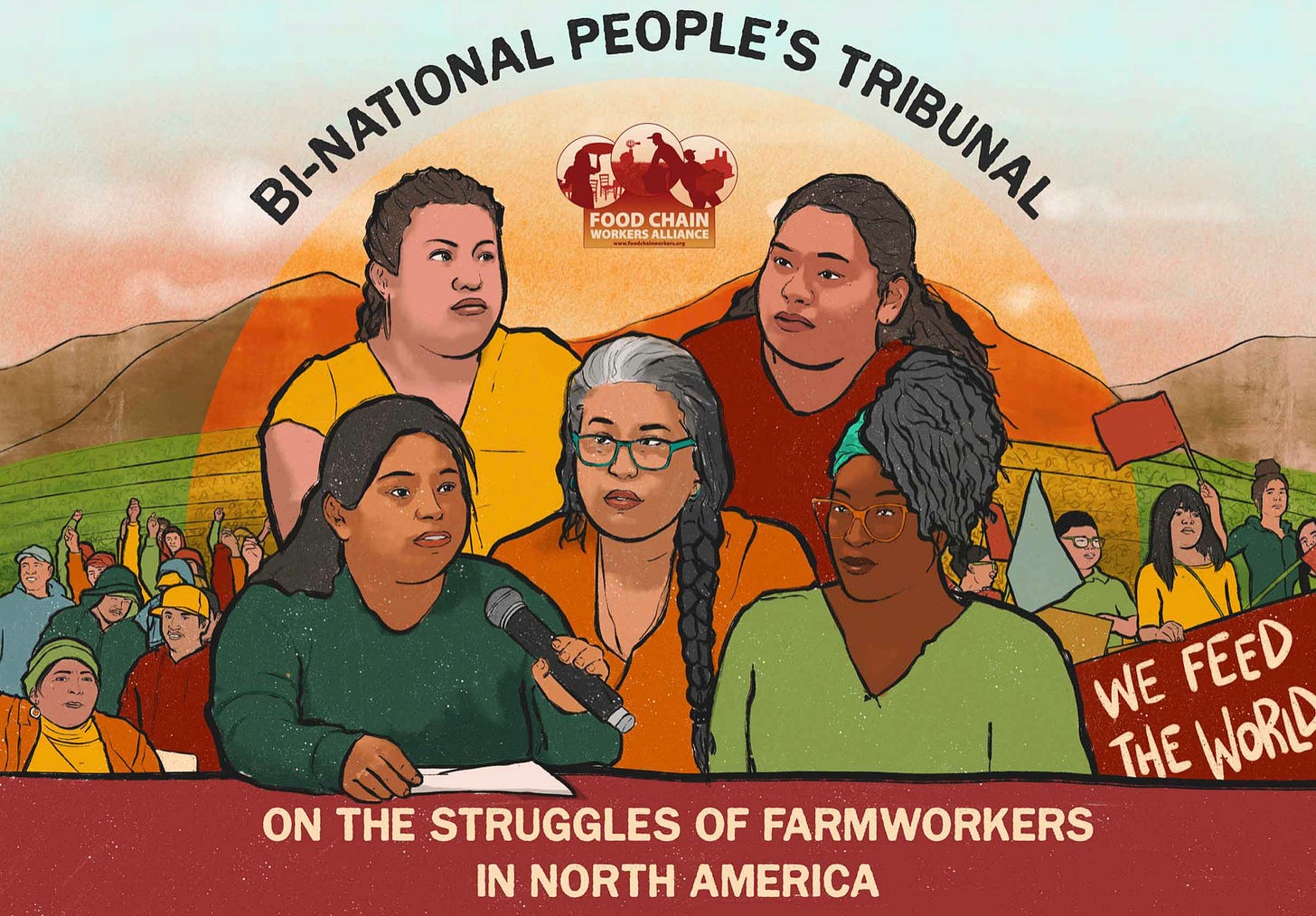

Recently, a historic tribunal was organized by the Farmworker Committee of the Food Chain Workers Alliance (FWCA) to unite and amplify the voices of farmworkers across North America and beyond. FWCA is a grassroots organization founded and led by supply chain workers, with hundreds of thousands of members. They are among the most compelling movements in the food industry and need our support. This content was generously shared by FWCA with The Checkout Grocery Update to spur support for the people who grow our food.

What Is A Tribunal?

Tribunals are forums set up by social movements, communities, and organizations to bring attention to the truths with which our judicial and political forums either cannot or choose not to engage. They shed light on and amplify human rights violations, as well as a vision for addressing those violations.

Around the globe, hundreds of millions of food workers make it possible for the world to eat. Almost all the food we eat passes through the hands of workers who plant, harvest, process, package, transport, prepare, sell, and serve. As detailed in the report No Piece of the Pie: U.S. Food Workers in 2016, in the U.S. alone there are more than 21.5 million workers along the food chain, making the food industry the largest employer. It’s also one of the most exploitative.

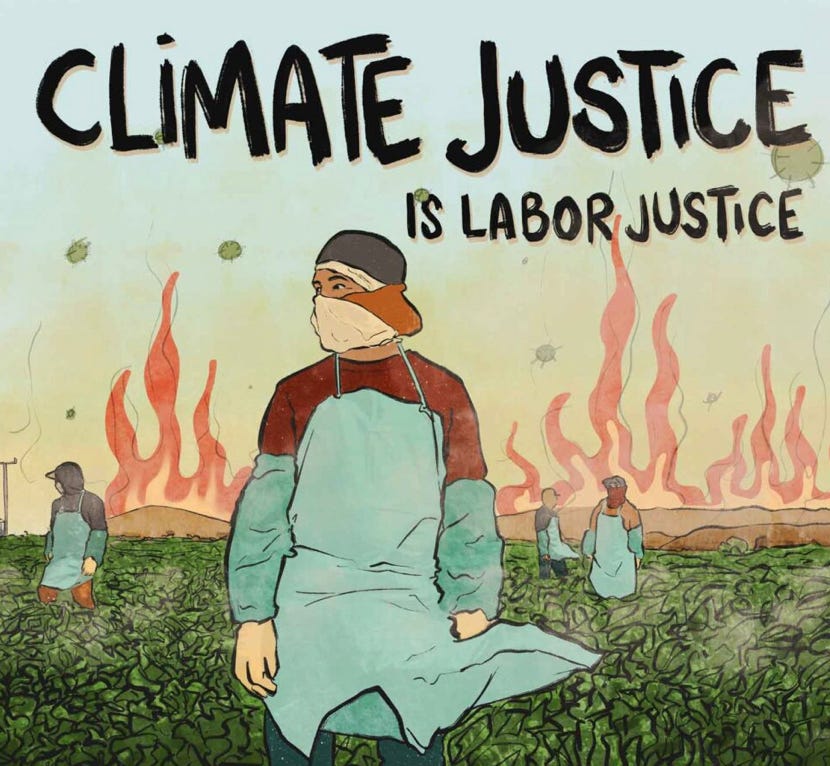

Food workers receive the lowest median wage of any working group and they are also more dependent on public assistance. They are subjected to dangerous working conditions with high rates of injury, death, and illness. They are also greatly impacted by climate change, from rising temperatures in the fields and workplaces to climate disasters such as wildfires. These conditions, along with increasing precariousness and a lack of job security, leave food workers vulnerable to wage theft; racial, ethnic, gender discrimination; sexual harassment; and violence.

Housing.

In a 24/7 industry like dairy farming, employers normally provide on-site housing for workers. Maira, a former dairy worker and organizer with the Workers’ Center of Central New York (WCCNY), spoke about the dangers and hazards of farm housing:

“The biggest problems are pests, lack of space, broken windows, no heating, no privacy, failure of machines such as washing machines and refrigerators. The lack of privacy and cleanliness is what affects people the most, especially families.”

“The homes are not safe for children, but the employers accept children because they need the workers to be stable, and to not leave the farm easily. A worker without family and children is more likely to leave the farm. Many are grateful to be allowed to have a family there, but the truth is that the bosses exploit the situation.”

Bathroom Access.

Claudia, a former farmworker and Director of the Pioneer Valley Workers Center (PVWC), spoke about a chronic lack of bathroom access that is not only inhumane in the short-term, but can also cause long-term health problems:

“One of the most serious health and safety problems is the lack of toilets in the fields. Not only they are far away, but we have to walk a lot to get to the bathrooms. Sometimes they are very dirty… The main problem is that you don’t have time to go because there is always a supervisor rushing.”

“A couple of women workers had to go to the hospital because they couldn’t wait to go to the bathroom because they got a urine infection. The doctors told them to drink enough fluids, but they told them that they were restricted from going to the bathroom at work and that they couldn’t drink water for that reason. None of the workers wanted to tell the boss because they knew that he would not pay attention to them.”

Workplace Injuries.

Due to a lack of adequate health insurance, fear of immigration authorities in hospitals, and employers that deny workers’ compensation, workers in Canada and the U.S. are rarely able to rely on the healthcare systems despite the fact that they often incur injuries on the job.

Moilene, an organizer with Justice for Migrant Workers (J4MW), shared multiple stories from workers in Canada:

“I fell from over 9 feet and was stuck with multiple injuries. The employer knew the doctors at the hospital. They had friends at the workers’ compensation board and they had friends in the liaison office, so [I] had nowhere to turn.”

“When I got an injury at a pumpkin farm, one of the employees called the boss and told him that I got injured. [The boss] didn’t really come there quickly… I told him I was really really dizzy and not feeling good. The only thing the boss wanted me to do was go back to work. He didn’t ask me if I wanted to go to the hospital. He didn’t bring a first aid kit or anything. He just wanted me to go back to work.”

“A cow got scared and pinned me against the tubes, damaging my back. She pressed me all against the tube and was stepping on my feet. The cow didn’t move, and I couldn’t move my arms. The cows weigh about 400 or 500 kilos. No one helped me, there was an American worker who ignored me. I turned around as best I could. It lasted about a minute. I thought I had completely broken my body. I couldn’t walk, I didn’t call 911, just texted the boss. The only thing he said to me was: ’Did this happen at work? Who is going to cover you? Do you have someone to cover you?’”

Sexual Violence.

Farmworker members testified that sexual harassment of farmworkers is not talked about because it mainly affects women. Women have reported being touched without their consent while they sleep, being raped in their rooms, being offered better work schedules in exchange for sexual acts, being harassed and threatened while they are working, and having their weekly pay withheld by supervisors unless they agree to go out with them.

Patricia, a former farmworker and organizer, shared a specific incident:

“When the other woman left, she was the only one among 13 men. The boss had a room where there was no door for her, the room didn’t have a door, only a curtain. There was a man who, when she came home from work, she was tired and went to sleep, this man would come and start touching her. She felt desperate and stayed still, because many times he was drunk… It is an unbearable memory for her. She asked the boss if he could put a door with a lock in her room so that wouldn’t happen, but he never did.”

Patricia also shared her own experience:

“I started working on a farm where a man who was in charge made a lot of advances toward me and told me that he wanted to go out with me. I told him that I wasn’t interested. At night he sent me messages that he wanted to go out with me, and I told him no. And he told me ’I have your check, if you want it, you will accompany me out one day.’ At the end of the week, he paid everyone except me… He told me one day ’you think you’re too good for me? Don’t you know that I can make you lose your job?’”

Fear of Deportation.

Luis Jiménez, a dairy worker and co-founder of Alianza Agrícola (AA) stated New York is also a border state where border control is omnipresent and workers are at risk of detention. The collaboration between Border Patrol and the police means that for workers there is little distinction between the two. When workers organize, employers threaten to call the police, and by extension, immigration.

Luis also shared that under the Trump Administration, bosses restricted workers’ movements if they did not have a driver’s license, for fear of workers being detained:

“But this does not mean that the bosses are good people and want to protect us, but rather that they do not want to be left without workers. On the contrary, we will never see bosses fight for a permit for us, or for immigration reform. With a work permit we would be more independent, we could organize ourselves more easily, or we could look for another job more easily. The bosses don’t want to lose control, they will never advocate for a permit for us, but they will advocate for the expansion of programs like H-2A.”

After extensive organizing, workers in New York won the right to access driver’s licenses regardless of immigration status in 2019. Luis shared that this has been one stepping stone to freedom of movement for farmworkers in the state:

“For us, winning the right to have a license was difficult, and even though it was a victory because some people have lost some fear, the reality is that it is not the solution to the problem, the fear continues. Thanks to collaboration and participation of many allied organizations supporting our work, we have been able to achieve many changes in the community to protect agricultural workers, the immigrant community, but I think we should have more freedom.”

Juan testified about undocumented farmworkers living with the constant underlying worry of deportation:

“It is like a threatening giant that makes people psychologically ill. It is believed that half of the agricultural workers do not have the documents that protect them. Therefore, we have lived in the shadow of fear. In the current administration, thank God, we have lived a little peacefully, but we have not stopped worrying because we know that later on our peace of mind will be broken again and fear will invade us again in the fields, at home, on the street, wherever we go.”

Alfredo, a farmworker and organizer with Community to Community Development (C2C) in Washington described how workers are organizing to oppose the expansion of H-2A in the state. Through their work with farmworker communities, C2C and Familias Unidas por la Justicia (FUJ) have seen the impacts on guestworkers and local farmworkers and their families. The H-2A program relies on an extreme form of employer control wherein workers are isolated, have their passports seized, and cannot exert labor mobility:

“People are moved from their home to a place they don’t know to work a lot of time under extreme conditions without proper equipment to stay safe. There is a lot of wage theft. They usually don’t have any connection with other people that live around the place where they stay. The company that brings them here holds on to the worker’s passport, at any point that those workers do things that the company doesn’t like they — the workers — can get deported at any time. They could be put on a blacklist where they can’t apply to work at any company in the U.S. ever. H-2A workers don’t know their rights. Those that speak up are threatened with being deported. Because of this H-2A workers stay silent.”

Alfredo added that even though hiring H-2A workers costs employers a lot of money, companies would rather use the program than pay local workers a better wage because of the control they have over the workforce:

“Companies claim they have a labor shortage and must use H-2A workers to meet their needs, while making it very difficult for local farmworkers to apply to jobs and reducing the number of hours given to local farmworkers.”

Extreme Temperatures.

Many of the testimonies in this session revealed the very real ways that workers are currently being harmed by extreme temperatures:

“At work it was so hot, I could see the heat wave. I passed out more than once from the heat that was there. I don’t know what happened. I think by that time the ambulance came there, and they said nothing. Everybody just got back to work. You’re not allowed to take water in the field. You can’t get access to your things if you need it. Other people had fainted as well. You just had to do what the employer said.”

“Many people stay silent to keep their jobs. From May to August the temperatures are almost unbearable, we are talking about 100 degrees or even 105 degrees, and the pace of work is more intense.”

“OSHA may have regulations for high temperatures, but the cold is also extreme for some industries like dairy. Many people may not pay as much attention to the cold, but it should be taken into account. The work is more complicated during the winter. What you do in the summer in half an hour, in the winter it takes you about an hour or more. We are sometimes in open places where the air is very aggressive. Maybe those who don’t milk the cows don’t realize, but those who milk know that the floor can freeze, the machines freeze and you have to put your hand in hot water and that affects us. The accidents that happen due to low temperatures are: blows, people slip, your bones hurt, you can’t breathe. The water would freeze inside, the workers have to buy their own portable heaters, and so you have to find a way to stay warm.”

What Next?

“Justice, Justice you shall pursue.”

At The Checkout Grocery Update, we will continue to stand with food workers and share our platform so they can speak for themselves and push for the changes they want to see in their work and livelihoods. Stay tuned for more.

3. Kimchi Of The Week.

This week’s champion kimchi is a tie between these two killers from H-Mart. Stuffed cucumber kimchi is the best of both worlds, salty, juicy, pickled cucumbers stuffed with mildly hot fermented chili peppers. And radish kimchi is sweeter, crisper and more refreshing than the usual napa cabbage. Each goes great with ramen, eggs, stir fried veggies, home fries, some bibimbap or on a sandwich or taco. Really tasty.

4. Seen In The Wild.

Meanwhile, somewhere in Texas, pricing signage like a champ.

5. Tunes.

Forty or so years ago, before the age of tech broligarchs, retinal scans, AI mindfuckery and drone swarms, the metal gods Judas Priest described our digital surveillance hellscape quite presciently.

peace.