Grocery Update #39: The High Cost of Cheap Food. And The Historic Halting Of A Grocery Merger.

Also: An Autumn Apple Smackdown. Because We Love Apples.

Discontents: 1. The Historic Halting of the Kroger-Albertsons Merger, with Professor Shane Hamilton. 2. The Cost of Cheap: A Call to Action for the Global Food System, by Heather K. Terry. 3. Autumn Apple Smackdown. 4. Tunes.

Happy Holidays! The Checkout Grocery Update Will Return In January 2025. Saltier Than Ever.

1. The Historic Halting of the Kroger-Albertsons Merger, with Professor Shane Hamilton.

By Shane Hamilton and Errol Schweizer

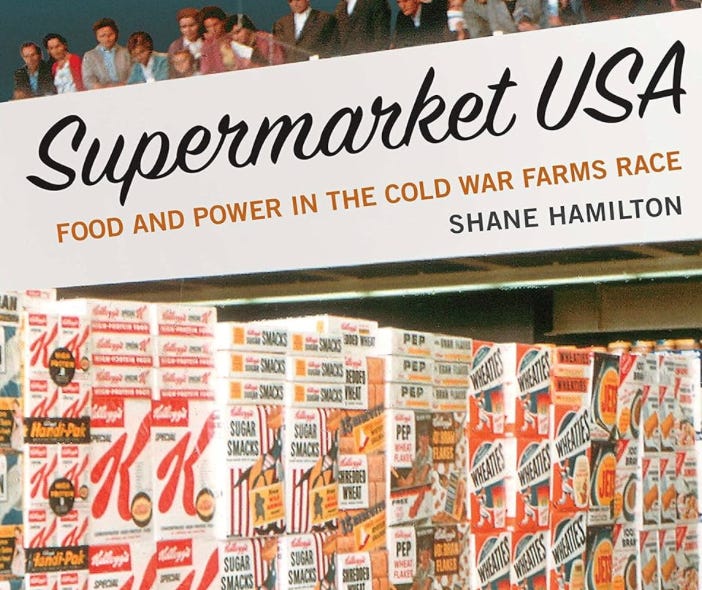

Shane Hamilton teaches strategy at the University of York School for Business and Society, and is author of Supermarket USA: Food and Power in the Cold War Farms Race (Princeton, 2018).

Errol Schweizer is publisher of The Checkout Grocery Update.

On December 10, a federal judge in Oregon and a state judge in Washington issued injunctions that have now permanently blocked a merger of supermarket giants Kroger and Albertsons. These decisions have been hailed as a victory for the Federal Trade Commission, which argued that a merger would harm consumers who are outraged at the rising cost of food. But in a historically significant twist, the courts’ decisions should also be understood as a victory for workers and entrepreneurs, pointing the way forward to a fairer and more innovative food system. Strikingly, the FTC’s intervention draws lessons from the past to shape the future.

From the 1930s into the 1960s, American supermarkets were routinely touted as exemplars of free enterprise. Initially derided as “price wreckers,” operating on a “stack ‘em high, sell ‘em cheap” business model, by the 1950s America’s supermarkets were the envy of the world. Offering affordable abundance to consumers, supermarkets were upheld as Cold War “weapons” against communism -- concrete demonstrations of the power of private enterprise to bring “luxury to the masses.”

But at the same time, both ordinary Americans and government policymakers understood that the supermarket economy was anything but a “free” market. Workers and consumers joined together to challenge waves of consolidation in food retailing in the late 1950s and early 1960s, insisting that low prices should not come at the cost of reducing workers’ wages. Small businesses--including farmers, food processors, wholesalers, and independent retailers--also expected government antitrust enforcers to intervene in the marketplace to promote competition. Small, regional grocery chains, attuned to their local customers’ interests rather than distant shareholders’ demands, were often the most innovative businesses in the industry, introducing such novelties as telescoping shopping carts and frozen foods initially shunned as too risky by larger firms like Safeway and A&P.

Until the 1960s, antitrust enforcers had a broad range of tools at their disposal to address these diverse stakeholders’ interests. Antitrust was messy, imperfect, and very complicated, but it was vigorously pursued under a widely shared understanding that the “free market” would not work if it were dominated by a handful of giant corporations. The Robinson-Patman Act of 1936 empowered the FTC to protect the interests of businesses that supplied supermarkets, while the Department of Justice used lawsuits and consent decrees to balance the concerns of workers, consumers, and businesses small and large. The Supreme Court’s 1966 decision in Von’s Grocery provided the FTC with sweeping powers to prevent mergers in food retailing, insisting that government support of small business was a desirable and necessary feature of American capitalism.

This faith in antitrust began collapsing shortly after Von’s. Legal and economic theorists including Richard Posner and Robert Bork influentially argued that consumer welfare was the sole priority of antitrust enforcement. In the 1980s and 1990s, big food companies including Kroger, Safeway, and the upstart discount retailer Walmart took advantage of increasingly lax enforcement of antitrust laws to consolidate their power in the industry.

Today the consequences are clear. Two-thirds of all grocery sales in the U.S. are controlled by six companies. Grocery retail is also heavily consolidated on a regional basis, with less than 3 companies controlling the majority of sales in dozens of metro areas. Retail workers’ wages have stagnated since the 1970s. A study of Kroger workers showed 75% faced food insecurity and 14% faced homelessness. Walmart Supercenter openings lead to a 16% increase in poverty, a 16% increase in reliance on government benefits and a 6% decline in household earnings. Consumer food prices have risen 30% since 2019, and grocery profits hit record highs in 2021 and 2023. Meanwhile, four or fewer corporations control 75% of yogurt sales, 93% of soda, 80% of candy, 60% of snack bars, 66% of frozen pizza, and 60% of bread. Scale begets scale. Dominant, incumbent brands can afford the massive marketing expenses demanded by the largest supermarkets, including slotting fees, promotional placements and retail media, limiting the opportunities for entrepreneurs to develop more diverse, sustainable and socially just innovations.

The free market clearly isn’t working in the American food system.

In this context, executives of Kroger and Albertsons insisted that a merger would enable them to gain even greater concentrated buying power, putting them on a more equal footing with Walmart. Such claims were rooted in the post-1960s transformation of antitrust policy that, under the guise of supporting consumer welfare, largely benefited the executives and shareholders of the largest food chains.

But under the leadership of Lina Khan, the FTC has flipped the script, reviving the historical lessons of the early decades of supermarket innovation. Court injunctions against the Kroger-Albertsons merger demonstrate that it is once again possible to use antitrust law to pragmatically balance the interests of consumers, workers, and a wide range of business owners and managers. The FTC calls this “reality-based antitrust enforcement.”

This may be the start of a new era.

The FTC is now pursuing a case against alcohol distributor Souther Glaziers for violating the Robinson Patman Act and engaging in “anticompetitive and unlawful price discrimination” against small businesses. The case may have huge reverberations in the grocery sector, which is monopolized by a handful of distributors with remarkably similar business practices to Souther Glaziers.

American supermarket shoppers, organized workers, and small business owners have every reason to hope that this pragmatic approach marks the beginning of a new economic reality--one in which claims about “free markets” are no longer patently absurd.

2. The Cost of Cheap: A Call to Action for the Global Food System.

by Heather K. Terry

Founder & CEO GoodSAM Foods

This past week, our U.S. team was back in Colombia, connecting with our beloved Colombian team members, leaders, farmers, and investors. These visits are always a source of renewed insight and inspiration. Spending time with different stakeholders reminds us why we do this work—it recharges our commitment to growing GoodSAM and pursuing a model of business that prioritizes people and planet over profit.

But make no mistake: working in agriculture to bring food products to the U.S. comes with immense challenges. Even in the U.S., our work with American farmers is rife with issues: a lack of financial resources, the greed embedded in our food system, and the exploitation of undocumented workers who are essential to keeping prices low. It’s all built on a foundation of inequality and a deeply ingrained mindset that food must be cheap—so cheap that we fail to question what this affordability truly costs.

The Global South: A Deeper Struggle

When we look to the Global South, where GoodSAM does the majority of its work, the challenges grow even darker. These regions contend with layers of complexity: illegal armed groups, the narcotics trade, endemic corruption, and unspeakable violence. For many of us in the U.S., it’s almost impossible to comprehend these realities. We sip our morning coffee without questioning its journey. Yet, the question we should be asking ourselves—especially those of us in the food industry—is this: Is someone risking their life to get this coffee into my home?

The answer, heartbreakingly, is yes. Across Latin America and the African continent, people risk their lives every single day to bring us everything from coffee to cacao, from avocados to bananas. Often, the cheaper the product, the greater the suffering behind it.

The Cost of Advocacy in Colombia

Colombia exemplifies this struggle. In the past two years alone, the country has witnessed the murder of 360 community, Indigenous, and agricultural leaders. In 2021, at least 145 social leaders and human rights defenders were killed, and this tragic trend escalated to 215 killings in 2022—the highest toll ever recorded. These leaders, many of whom defend land rights and sustainable farming practices, face threats from illegal armed groups vying for territorial and economic control.

These are not just statistics; they represent real people—leaders like José Mora, who gave their lives for their communities and their causes.

One of our most trusted leaders in one of the largest growing regions we source from, José Mora, was murdered. José wasn’t just a business partner; he was someone who believed in us when no one else did. He took a chance on our vision when others doubted it would ever work. José was killed while traveling between two regions, carrying cash to pay the farmers we work with—a sum so small that most of my colleagues in the U.S. would laugh at its insignificance.

His death is a senseless tragedy. It is infuriating and devastating. And yet, I know the questions that will come: Why was he carrying cash? Can’t you just solve this problem with technology or money? These questions betray a profound misunderstanding of the systemic challenges at play. In regions where banks are inaccessible, where digital infrastructure is a luxury, and where trust in formal systems is non-existent, cash is often the only option. And money alone cannot fix a broken system; it can even make it worse.

A Call to See, a Call to Act

José’s death has shaken me to my core. But it has also reignited my determination. This tragedy calls me to do something. It calls me to speak truths that are often avoided. Most importantly, it calls me to urge you to act.

If you work in the food industry, I challenge you:

Go see with your own eyes. Visit the farms where your ingredients come from. Walk the fields. Look into the faces of the people whose labor feeds the world.

Ask hard questions. Who is growing your food? How are they being treated? Are they safe?

Advocate for systemic change. We need more than fair trade certifications or greenwashed marketing campaigns. We need policies and practices that protect lives and livelihoods.

The Hidden Cost of Convenience

The next time you buy a bag of coffee or a bar of chocolate, remember this: there are humans around the world risking their lives to keep us fed. Nearly 152 million children are engaged in child labor, and 70% of them work in agriculture. In some regions of Colombia, farmers earn less than $2 per day—barely enough to survive.

We cannot continue to turn a blind eye to these realities. Food that is too cheap is not truly affordable; its hidden costs are borne by the most vulnerable.

José’s life mattered. His work mattered. And his death demands that we, as consumers and industry leaders, do better.

Join Us in Building a New System

At GoodSAM, we remain committed to building a food system that honors people, protects the planet, and values equity over exploitation. But we cannot do it alone. We need allies, advocates, and changemakers willing to step into the uncomfortable truths and fight for a better future.

Let’s make José’s legacy a catalyst for change. Let’s ensure that his sacrifice—and the sacrifices of so many others—is not in vain.

Are you ready to join us?

3. An Autumn Apple Smackdown.

Autumn is nearly over, but the apples are still crisp and fresh. So I popped on over to Central Market in Austin, Texas and bought a few. They were not cheap. But they were, for the most part, quite tasty. So here it is, my first ever…

Autumn Apple Smackdown.

Ratings on a scale of 1-5.

Pizazz: mild crunch, crisp bite, mildly sweet, pretty bland like a less sweet honeycrisp. 3

Pink Lady: sweet and floral, very dense and crunchy, slight tartness. 4

Kanzi: very crisp and tart, almost bitter, great bite and texture. 4

Honeycrisp: very sweet, a little tart and very crisp bite. Very ok. Corporate apple. 3

Gala: bland and corporate, very middle of the road, and undifferentiated. 2

Fuji: mildly sweet and a bit mealy. Boring apple. 2

Golden Delicious: soft and sweetish, very mild, little tartness, mealy. I love them when they are underripe and greenish. This was a bummer. 1

Sweetango: tart and honey taste, sweet but not as sweet as a honeycrisp, with similar crisp bite. Nice and refreshing. 4

Granny: big crunch, very tart, medium sweet, punchy but not much depth, very basic and commodified. I usually buy them out of habit when stores only have honeys, grannies, galas and fujis. 3

Empire: very similar to Macoun but sweeter, crisper, tart, very fresh. Surprisingly good. 5

Rome: mildy sweet, rosewater, very dense and bit mealy. 3

Red Delicious: Red but not… delicious. Maybe name should be in air quotes, like “to serve and protect” on cop cars? Bland, mealy, undifferentiated. Why does anyone still grow these terrible apples? 1

Opal Gold: unique taste, almost taffy or candy like, very sweet, not tart, crisp and dense. 4

Lady: tart, mealy, crabapple vibes, but sweeter, almost pear like. 2

Macintosh: my standard bearer, tart and sweet, pretty balanced, slightly mealy but heavy crunch. 4

Macoun: very balanced, tart and sweet not too much of either, deep crunch, refreshing, I admit this is still my favorite. Highly underrated. Cvlt apple. 5

4. Tunes.

It is almost Hanukah, so it is time for my favorite song mentioning Jewish food. And while latkes would be much more seasonally appropriate, I believe the tastiest Ashkenazi-heritage vehicle for potato consumption is the knish. Just a humble bundle of mashed potato wrapped inside a comforting doughy blanket. Like a big, chubby potato empanada or an oversized baked pierogi. And the greatest tune about knishes is by the late, great MC, MF DOOM. The coolest part about this track is that the guest MC, the mysterious Mr. Fantastik, steals the show, slinging some of the greatest verses and flows in human history. Happy Holidays, Rapp Snitch Knishes!

peace.

“Chubby Potato Empanada” is a pretty good rapper name