Grocery Update #13: Three Rivers Market and Knoxville's Grocery Scene

Also: The Whole Story Book Review + How Emerging Brands Can Survive The Private Label Wave

Discontents: 1. Three Rivers Market and Knoxville’s Grocery Scene. 2. How Emerging Brands Can Survive The Private Label Wave. 3. The Whole Story Book Review. 4. Tunes.

1. Three Rivers Market and Knoxville’s Grocery Scene

I love driving through Tennessee along I-40. It is among the most beautiful states, all trees, parks, rivers, rolling hills and ancient, dramatic Appalachian ridges, with the occasional confederate knuckle-dragging. On the eastern fringe of the state, flanked by Oak Ridge and the Great Smokies, is Knoxville. Knoxville is a diverse, blue collar town with a cool music scene and an overabundance of brewpubs. It is legit Appalachia, unlike J.D. Vance’s fake bootstraps. There are no shortages of grocery stores in Knoxville. Mass merchants Walmart, Kroger and Publix, regional chain Ingles and discounter Food City, upscale Fresh Market and plenty of Aldi, Trader Joe’s and dollar stores.

I decided to check out a few grocery stores on my road trip after a staffer at Three Rivers Market, a consumer owned cooperative in Knoxville, sent me a nice note pumping up their commitment to local sourcing and food justice:

“Three Rivers Market is redefining the concept of offering high-quality, locally sourced products in Knoxville. Since 1996, it has been committed to setting new product quality and sustainability standards. Its rigorous selection process ensures that every item on its shelves meets its stringent criteria for freshness, organic certification, and local sourcing. What truly sets them apart is their dedication to transparency and community engagement. They don't just sell products; they build relationships with local farmers and producers.”

Oh really? Those are some tall claims. I needed to see this.

But first, I popped into a couple of similarly positioned grocers, Whole Foods and Earth Fare, just to get a relative sense of the scene.

The Knoxville Whole Foods is like an old pal. I have been shopping there for years as a stopover in road trips between New York and Texas. Right off the highway, the store has always been well stocked, clean and bright, with friendly staff and a good selection. Along with the Green Hills store in Nashville, the Knoxville store has always been one of my favorites. I am glad that although Amazon has really gutted a lot of stores, especially in Austin, Boston and New York, there are still Whole Foods that feel like Whole Foods. I bought a few staples on this visit and was not disappointed with the staffing. A clerk at the cheese counter, Kate, was super helpful and enthusiastic, even though I wouldn’t buy any of the products she was recommending. That is the Whole Foods I remember.

Next stop on my mini-Knoxville grocery tour was Earth Fare. Founded in 1975 and based over the mountains in Asheville, Earth Fare went belly up in 2020 and was restarted shortly after, quickly expanding to 20 stores. Earth Fare in my mind was always an old school natural foods store, like Gooch’s, Wild Oats or Sunflower, chains that have long since been acquired (Whole Foods and Sprouts, respectively). Now, Earth Fare has a premium positioning, not too different from Fresh Market, with higher end prices on mainstream brands balanced with plenty of value-tier private label and wholesaler brands from UNFI. The aisles were fronted, faced and well merchandised, the style a bit old school too, with 8 or 12 foot runs of products in the sets instead of the 4 foot blocks that most chains have evolved into.

They had some great seasonal deals and it really felt like summer in the store. Some displays felt a little light on inventory, including some understocked pallet drops and promotional kiosks that did not have mark downs. Like a $10 cereal that could form the wrong type of price perception, even if it is a good seller. While Earth Fare had plenty of organic produce, much of the conventional products took center stage in entryway displays. It was a bit confusing, especially since the prices were on the higher side. There wasn’t a clear differentiation for me, as a shopper browsing the aisles. What does Earth Fare stand for? I know they have been trying to be a leading innovator with emerging brands, which is much needed, but it wasn’t obvious on this visit.

And finally, Three Rivers Market. Three Rivers is part of the National Cooperative Grocers buying club along with over 200+ other members. There was plenty of Co+op deals propaganda and signage, with compelling pricing on popular brands. But what really caught my eye were two things: a focus on local suppliers and a clear segmentation of value-priced, mid-tier and higher end options, especially on the perimeter. Value wise, like Earth Fare, Three Rivers was rocking Field Day and Woodstock private labels which are built to match 365, Simple Truth or Trader Joe’s on price and quality. Mid-tier brand-wise, like Earth Fare or Whole Foods, Three Rivers stocked plenty of the usual suspects, like Frontier Spices, Nature’s Path, Annie’s and Eden Foods.

But what really set the co-op apart was exactly what they promised in their email to me, a big focus on supporting local growers, including several varieties of tomatoes, carrots and cauliflower. Local and organic cauliflower is a whole different ballgame from the industrial varieties that smell like trash farts when you cook them up. The co-op also had a full display of local honey. And although I did not partake, the co-op had a whole cooler of locally raised and processed meats, complete with humane standards and signage indicating what farms they came from.

The co-op also had bulk oxygenated water and a healthy selection of locally baked breads and pastries. The biggest display was a stack of locally brewed beer from over the hills in Asheville. Staff was also super helpful. Adam, a grocery clerk, talked me up about smoked trout and everything else within reach. It was great to see this enthusiasm at the store. Three Rivers also had its own brand of supplements and a throwback apothecary assortment of essential oils, flower remedies and homeopathics that are getting harder to find. The customer base at the co-op also felt the most diverse and interesting. Whereas Whole Foods was a bit more upscale and high touch, the co-op felt like Knoxville: gritty and friendly, just come as you are. And like any good co-op, Three Rivers had plenty of messaging about their community support programs, like funding the public library and helping to alleviate food insecurity. With publicly funded programs usually falling short, sometimes we need to kick in some grassroots support to keep these alive.

Overall, Three Rivers delivered on their promises. It was good to see a community owned store firing on all cylinders. I would definitely shop there if I lived in Knoxville, and will be stopping by during future road trips.

2. How Emerging Brands Can Survive The Private Label Wave

Originally published in NOSH.

Emerging brands must stay distinct from their peers while navigating cut throat category management requirements, high wholesaler fees and competitive pressure from packaged food monopolies that dominate market share. Store brands, which had once been all about low prices and generic offerings, are now leveling up with eye catching design, better formulations and sustainability claims. While consumers may benefit from better products at better prices, it also means more challenges for emerging brands in a long and difficult road to success.

So what does this mean for CPG start-ups and emerging brands? There are two potential strategies that could them insulate from the store brands deluge.

First, is to build a "moat" around the brand. In another words, you need a defensive perimeter that keeps competitors at bay. This could be a unique and compelling formulation, a clear and sticky connection with a specific customer segment or consumer need state or any other leading distinctions that set your brand apart. Examples of this include Magic Spoon, a low carb, high protein cereal actually made from milk. Or Siete Foods, who combines grain free pantry staples with their Rio Grande Valley heritage.

The other, contradictingly, is to build community beyond your little brand fortress. This could be through advocacy for issues important to you, your suppliers and/or your customers. The most obvious example of this is Ben & Jerry's, but also Manitoba Harvest (on hemp legalization), Tony's Chocolonely (on child labor, however imperfectly). None of these brands make the best products, but their advocacy positions were important to their success.

A brand that does both of these things well becomes genuinely unfuckwithable and iconic. The easiest example here would be Dr. Bronner's. They control their own supply chain, make their own products, including best in class soaps that make your tookis tingle. They also put money, time and energy into issues that matter to them and their customers, such as drug legalization, regenerative organic farming and environmental preservation. They have succesfully fought off store brand incursions for decades while not compromising quality or value.

This doesn't mean its easy. But surviving the store brands tsunami is definitely possible for emerging brands who can stay a breed apart while building bridges with their consumers.

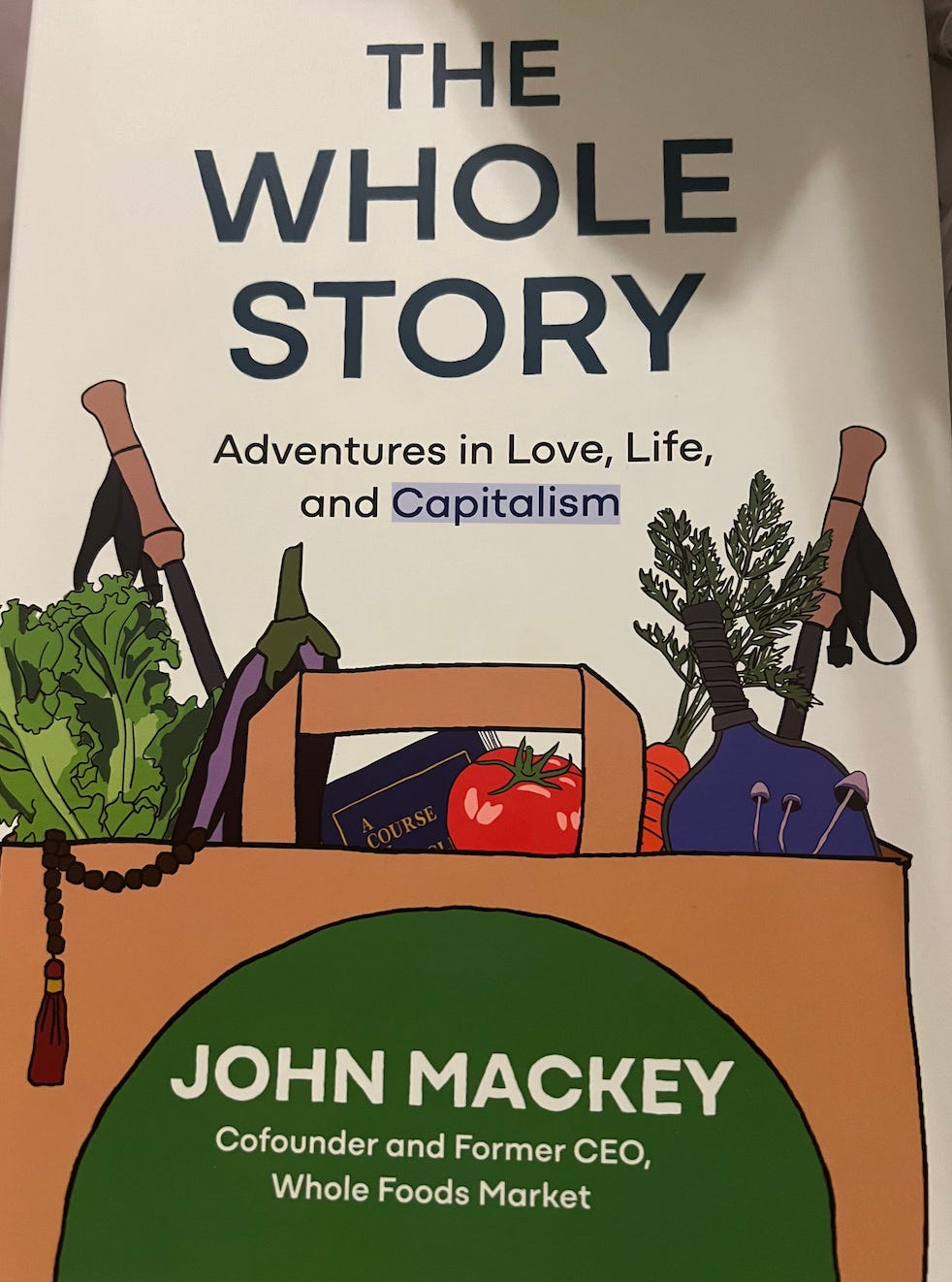

3. Book review: The Whole Story by John Mackey

This is an expanded and unabridged version of a recent review published in Forbes, exclusive to readers of The Checkout Grocery Update.

My supervisor had warned me and I hadn’t listened. “Don’t challenge John, he will bite your head off.” I was a young grocery buyer, just starting on the national merchandising team. I had been with the company 6 years, bouncing around and up from stock clerk through 4 stores and 3 regions into a high pressure job in Austin. We had just gotten out of a full team meeting after a tough quarter during the great recession. Our CEO, John Mackey, addressed a couple hundred of us directly about the state of the company, which at the time was decentralized into 12 operating regions in the U.S.

Mackey, or as some of us called him, “The MacDaddy” liked to tell stories during meetings, evangelizing his vision, but occasionally veering off into more ideological territory around personal responsibility or whatever he wanted to riff on. It was usually pretty entertaining and occasionally informative. I decided to raise my hand and ask a question, something along the lines of why the communication was so poor between our stores, regional offices and the national teams. I gave a few examples. As I was warned, he did not take it well. His response was along the lines of, “how dare you suggest that, what is wrong with you, you are absolutely incorrect, etc.”, in front of a couple of my hundred peers. Oh well. I guess I hadn’t been vibing with the story.

But CEO’s have to be good storytellers. Like Bible Belt fire and brimstone preachers, CEO’s know that nothing binds the flock better than a good yarn. John Mackey’s vision, through his gift for storytelling, enabled Whole Foods to change the way America eats, buys and thinks about foods. But not all good stories have happy endings.

According to The Whole Story, Adventures in Life, Love and Capitalism, Whole Foods was founded in 1980 as Saferway. The moniker was a glib jab at the mainstream grocer now owned by Albertsons. An infusion of his father’s money, support from buddies in the oil and gas industry (this is Texas after all) and an eventual merger with another local grocer kickstarted the Whole Foods legacy. The company attracted an eclectic and colorful workforce, an atypical ensemble of artists, veterans, musicians, scientists, graduate students, college dropouts and “more than a few closet socialists” (how scandalous!) who collectively made the company the most compelling retail success story of the late 20th and early 21st century. Mackey places himself at the center of the story, (“it’s really my story”) as a leader, observer, critic and active participant in the company’s rapid growth, evolution and eventual acquisition by Amazon.

The Whole Story is history from above. It is about the of kings and queens (mostly kings), their retail conquests, alliances, quarrels and fiefdoms, sans dragonfire. These include several generations of his proteges and collaborators, who get credit for their successes and triumph’s. This includes former President and COO AC Gallo’s innovative perishables merchandising that transformed how almost all grocery chains display fresh produce. Mackey also recounts his rivals who rose through the ranks and took an L when they challenged him for the throne. And he includes Paul Rice, who is introduced as the face of Fair Trade USA, while the millions of Global south farmers using such mutually beneficial trading relationships to lift themselves out of poverty remain invisible. The story even cameos Howard Schultz, CEO and Founder of Starbucks, who sent Mackey a hellfire nastygram in 2016, demanding he step aside and stop ruining the company. By Mackey’s own account, Schultz’s criticism was just echoing that of many of Mackey’s rivals through the years, with little self-examination of the pattern. In Schultz’s case, his friend and confidant, Whole Foods co-CEO Walter Robb took the fall for this stunning act of hubris.

The Whole Story is the story of Strider, Mackey’s trail name, the secret king as he triumphantly strode up the Appalachian trail while trusting thousands of Whole Foods team members to mind the stores. It is also the story of “Rahodeb”, a CEO who couldn’t stop trolling stock trading message boards late at night.

The “life and love” subtitle is accurate too, there is plenty of interpersonal drama, marriages, break-ups, hook-ups, but thankfully, no drug-fueled orgies. There is a sprinkling of age-appropriate boomer cringe (“selling ice to eskimos”) and casual racism (a couple references to majority Black/Latino East Austin as a “bad” neighborhood) and plenty of gushing and philosophical stroking of capitalism as mankind’s greatest invention.

There is the expected anti-union bluster, out of touch with nearly 80% of Americans, but feeding the cognitive biases of the core audience for the book: hungry, incipient CEOs, their proteges and accomplices. One anecdote recounts a time at the Madison, Wisconsin store when a local college professor challenged his students to unionize Whole Foods. The union campaign was immature, awkward and ultimately doomed. Mackey learned quickly, touring the company, realizing his employees needed better pay and benefits. And he delivered. But would he have been thus enlightened without the union drive? Unions are highly imperfect but effective. They are voluntary associations run for the mutual benefit of their members, improving pay and conditions across whole industries. They are only “compulsory”, as Mackey calls them, when employees vote for them and drag CEO’s to the bargaining table. In Mackey’s story, the union “gangsters” cliches run loud and large, still echoed by the billionaire Schultz’s, Musk’s and Bezos’ of the world. A velvet idealism that all “can work together as partners, fellow stakeholders, with openness, trust, community, shared purpose, joy and love” hides Mackey’s razor sharp focus on expense management. Union free, during the Fresh Fields acquisition, the “first order of business was to cut their bloated support staff”.

The reader should be advised then, that there are few cashiers, clerks or janitors in this story, ostensibly about a chain of grocery stores. As the company scales and industrializes, the staff disappears into abstracted “team members”. Hence, this is not the story of George Martinez, a longtime bulk foods buyer who kept the bins full, clean and rotated for over a decade before being laid off during the pre-Amazon 2015 restructure. This is not the story of Todd Bamberg, an excel whiz whose 2007-era “duct tape and baling wire” merchandising spreadsheet templates are still being used by the buying teams today. Nor is this the story of Claire Sullivan, a former local foods buyer whose purchase orders helped reverse food apartheid and rebuild long dormant supply chains across the Hawaiian archipelago, lessening dependence on overseas imports. Like the Rush song goes, “And the men who hold high places, must be the ones who start, to mold a new reality, closer to the heart”.

The Whole Story reveals the secret sauce to the Whole Foods success throughout the early 2000s. “We were more ambitious and thought strategically about the long term”. Yet also cuddly, paternalistic and spiritual. Pathologically competitive, acquisitive and expansionist. Salary caps for executives plus broad, store team level “gainsharing” that shared productivity gains 50/50 with employees. And among the most equitable distributions of stock options for employees. Keeping morale and employee retention high and turnover low, AKA getting “Whole Foods fired” or being transferred to a less important job. Attracting generations of talent, who brought along their friends and families, creating networks of patronage that spread the vibrant retail culture from city to city and state to state. That it was better to apologize than ask for permission. That for thousands of employees, it was more than a job. It became a shared mission of selling the best food and changing how their world eats, a place where they fell in love, made friends for life, moved up into the middle class. John Galt in faded cargos, or maybe Sheldon from The Big Bang Theory as The Man In The Arena. Outwardly antagonistic to “anti-capitalists” and “left wing intellectuals” yet thoughtful and learning from their criticisms and unafraid to experiment, revolutionary in the most classically capitalist sense. Retail after all, means to “re-tailor”, from the French, always evolving, adapting. Capitalism, conscious.

Mackey was the CEO and capitalist who truly loved the game of capitalism, but not all the players. His justifiable, relatable, palpable disgust at the VC’s, activist investors, board members, retail competitors, and professional MBA’s trying to tell him what to do, trying to steal his company, screw his employees, ruin his vision and legacy.

The Whole Story is a tale of a brilliant retailer, smart enough to learn from those attracted to his orbit, who “wanted people to innovate, take risks, create great stores, manage them locally and surprise and inspire us all with their success”. A storyteller, evangelist and orator who inspired thousands of grocery workers to feed the world good food. Until the layoffs and restructuring.

That, then, is a story of how retail is just math, and you can ignore this math at your peril. The weighted average gross margins of millions of products, blended by department, dependent on their labor needs and supplier costs. Supermarkets have big center stores because big center stores are the key to supermarkets. Mackey’s Whole Foods model gloriously disrupted this, with large, gorgeous perishable sections that meant higher shrink, and fresh prepared delis and full service meat cases that meant higher labor. “Whole paycheck” was selling great food with stellar service at absurd prices, making organic mainstream, bringing thousands of innovative new brands to market, riding the consumer demand wave through multiple recessions until it all crashed on the rocks of capitalist competition, by trying to match Kroger, Walmart and HEB on pricing while imitating the Trader Joe’s store brands tsunami. As Snoop Dogg would say, “the math ain’t mathin’ “. After 20 years of being a “best place to work”, the retail math made layoffs, restructuring and centralization inevitable. Just as Amazon math later ensured greater bureaucratization and higher G&A (way more “bloated” than Fresh Fields), expendibility and high store level employee turnover, even higher rates of part-timer-ism, plus a shift to MBA/professional managerialism instead of blue collar upward mobility, and a loss of innovation and ingenuity at the store level. But at least, all still union free.

It is a story of how conscious capitalism, conceived by a free-spirited Texan, gave rise to the globalist, G7 stakeholder capitalism now derided as “wokeness” by Mackey’s fellow travelers in the conservative movement. This is a bait and switch almost as cute as when Romneycare was rebranded and expanded as Obamacare. And speaking of, there is the story of THAT WSJ op-ed, the one with the Margaret Thatcher quote, parroting Phyllis Schlafly and Heritage Foundation talking points against socialized medicine, with Mackey joylessly lecturing his liberal customers on personal responsibility and the superiority of free markets to deliver better healthcare, 40 million uninsured Americans notwithstanding.

Then, there is the sad story of his final days at Whole Foods, getting verbally decapitated by his boss, his new boss, an Amazon bigwig. A CEO who never had a boss before, this vegan alpha who never lost a challenge to his dominance, being told to expletively “just do what you are told” after questioning the received wisdom on remote work for white collar staff (Mackey thought it was a double standard relative to store employees). It would be funny if this humiliation didn’t presage the tragic death of the libertine, restless, crunchy, cosmic cowboy grocery culture dreamt up on long distance hikes, aided by LSD, MDMA and psilocybin under the warm Texas sun. Getting paid to sell good food while having fun doing it. Not Strider-as-Aragorn ascending the throne at Minas Tirith, but Gollum dancing maniacally, holding on to the one ring as he is swallowed by the fires of Amazon’s Mount Doom. A story for the ages.

4. Tunes:

Memphis is a long drive from Knoxville but it has the music scene I most relate to in Tennessee (yeah, I hate country music). While hip hop like Three 6 Mafia is the most relevant in recent years, Memphis soul is probably the most famous export, featuring Aretha Franklin, Earth Wind and Fire, and my favorite, Otis Redding.

peace.

Funny there is no mention of MacDdady hiding his identity and bashing wild oats stock in the forums illegally.