Grocery Update #113: Why BFY Grocers Are The Biggest Story In Food.

A Deep Dive Into the Broader Impacts of the Natural/Specialty Channel.

What readers are saying:

“Every newsletter is a masterclass. A must read for anyone who eats.” -Dan Barber, Stone Barns, Row 7

“Errol is one of the smartest, boldest, and most original voices in food. This is a must subscribe. “ -Mike Lee, The Future Market

“Errol has the freshest, most pragmatic, truth-to-power perspectives on the food industry, from an unusual vantage--decades of experience hip-deep in the grocery business, notably with Whole Foods Market. Always a bracing take on the everyday experience of filling your cart at the grocery store.” -Ken Cook, Environmental Working Group

“Fantastic insight and fun to read! Best Grocery Wonk in the Biz!” -Nova Wetherwax, Sacramento Food Co-op

“I really appreciate your focus on workers and getting into the weeds on the business-labor nexus.” -John Marshall, UFCW Local 3000

“wisdom, inc.”- BR

Why BFY Grocers Are The Biggest Story In Food.

By Errol Schweizer, Publisher.

Better-for-you or “BFY” grocers, also called “Natural/Specialty” grocers in syndicated data, are grocery chains that specialize in higher attribute products such as “all-natural”, organic, plant-based, humanely-raised and “better for you”, minimally-processed consumer packaged goods. That is what they do as retailers. It is not a niche or a store within a store concept, it is their core business.

While BFY grocers are still a small percentage of the grocery marketplace, under 5% in total, many such chains outperform the market in same store sales growth. Some have even increased their market share despite competitive headwinds and cost pressures. BFY grocers include national chains such as Whole Foods, Thrive Market, Trader Joe’s and Sprouts, sub-national chains such as Natural Grocers, Fresh Market, and Mom’s Organic Market, and regional grocers such as New Seasons, Fresh Thyme, PCC, The Wedge, Park Slope and other consumer-owned food cooperatives, as well as independent natural food retailers such as Kimberton Whole Foods, Jimbo’s and Good Earth. BFY grocers are setting the product standards and assortment mix that the rest of the market, even those with larger market shares, lower prices and much more massive supply chains, are racing to take advantage of.

BFY FTW?

It’s important to note that “BFY” is just a marketing term and is not scientifically validated. Are these products actually better for you? That remains to be seen, especially with the growing concern around the ultra processed foods links with chronic illness. But with a $1 trillion U.S. grocery industry system generating $1.5 trillion in health and environmental costs every year, BFY is as good a place as any to start figuring out how to make it all less damaging and hopefully more sustainable, at scale, in real time, at retail, where the overwhelming bulk of the U.S. populace interfaces with the food system. There is no better angle to influence the food supply, now.

BFY grocers are the best positioned to take advantage of generational shifts in consumer preferences on sustainability, health and wellness, and animal welfare. These consumer trends fly in the face of anti-sustainability efforts at the federal level, particularly hostility to food access, to the impacts of climate change on the food supply, or to animal welfare efforts and plant-based foods. For consumers, BFY products are a rare bipartisan point of consensus, particularly around organic and regenerative production.

BFY products have outperformed the rest of the market by almost 10 percentage points from 2021-2024. Products making “BFY” claims averaged 28% cumulative growth over the past 5 years, 40% higher than products without such claims. Products with “BFY” claims accounted for 56% of all growth over the last 5 years and grew faster than incumbent products in over 2/3 of categories. 58% of U.S. consumers now believe that issues like climate change and pollution are direct threats to their current and future well- being and 65% of consumers want companies’ sustainability practices to be more visible. 49% think sustainable products make a difference and 50% are interested in buying sustainable products (+5 pts vs. 2021). 64% of Americans are willing to switch supermarkets if their current store doesn’t offer humane alternatives to factory-farmed food and 50% seek out plant-based alternatives to animal products. 70% see environmental responsibility as more important and 90% of consumers see eco-friendliness as a key decision criteria. 78% of consumers aged 18-24 believe the current food system is not sustainable and a major cause of the climate crisis.

BFY Headwinds.

Income and wealth inequality are the main economic headwinds to BFY products and the grocers that focus on them. Wealth inequality in the U.S. continues to deepen, with a shrinking middle class, declining unionization rates, income stagnation, growing household and student debt, and a smaller number of ultra wealthy hoarding vast sums of cash and properties, much of it offshored. Just 10% of consumers are driving 50% of sales and there is an $80 trillion income gap for the bottom 90% of workers since 1975. Over 40 million SNAP recipients are being used as political collateral by the Trump Administration and 47 million Americans are already going to bed hungry and can’t afford enough food for themselves or their families. America is quite a horror show.

CEOs on the restaurant and QSR side of the food industry are seeing their customer bases bifurcate between haves and have nots, customers who can afford to eat out and customers who cannot. The grocery sector is even more polarized, with unit volumes down precipitously since 2021 as prices have skyrocketed. Grocers that lead with their value proposition are the fastest growing. Walmart, which controls almost 30% of U.S. grocery market share, has grown several points in share since the pandemic began. Aldi and Costco also continue to grow in share, sales volume and store count. BFY grocers have traditionally targeted that top 10% of customers but lately have been adjusting pricing and assortment to grab a more diverse share.

BFY Health and Wellness.

BFY grocers have benefitted from the post-pandemic awareness of health and wellness. Americans lived through a mass casualty event where over a million compatriots died, and most families were touched by sickness, disease, death or long term debilitating illness. Compounded with a lack of trust in a predatory, expensive and broken health care system, Americans are doing what they can to stay healthy, with the tools they have at hand, namely what they eat. It is not an ideal scenario, but people will try to control what they can when it comes to their health. Once mostly the domain of ponzi-schemers, new age hippies, Seventh Day Adventists and libertarian health nuts, wellness has gone mainstream. They can go overboard too, sometimes leaning a bit too far into “purity” and “cleansing” trends that have fascist sentiments.

Sprouts in particular appeals to “normie” consumers looking for healthier options. Their marketing is less sanctimonious than Whole Foods, not as weird as Natural Grocers and they can survive close competition from Trader Joe’s or Kroger banners while attracting a diverse customer base. Their “farmers market” store format, borrowed from earlier concepts such as Sun Harvest, Henry’s, and Harry’s, and centering bulk and produce departments, screams “healthy” compared to the typical supermarket with endless center store packaged food aisles and produce shoved off to the corner.

BFY Grocers filter and curate their product mix.

Whole Foods, Thrive Market and Natural Grocers have developed industry leading quality standards. Sprouts is not as well-defined, particularly in meat and deli, but their assortment is similar enough. On the one hand, this BFY merchandising strategy, via their own proprietary values-based purchasing rubrics, is self-fulfilling. The retailers promise a certain level of product quality and customers expect it, even feel entitled to it. But this market segmentation is also a double edged sword. It is not a populist appeal, but specialized and elitist. Customers need to have the impetus, education, income, transportation, motivation to make the trip. They don’t always shop BFY grocers for essentials, but for treats or impulse items or special purchases. What food access activists call “food apartheid”, where food choices are greatly influenced by wealth, educational attainment and geography, has benefitted these BFY grocers. America is a market-based society. It is based on inequality. If you can afford to eat well, you’re all set.

BFY Standards And Regulatory.

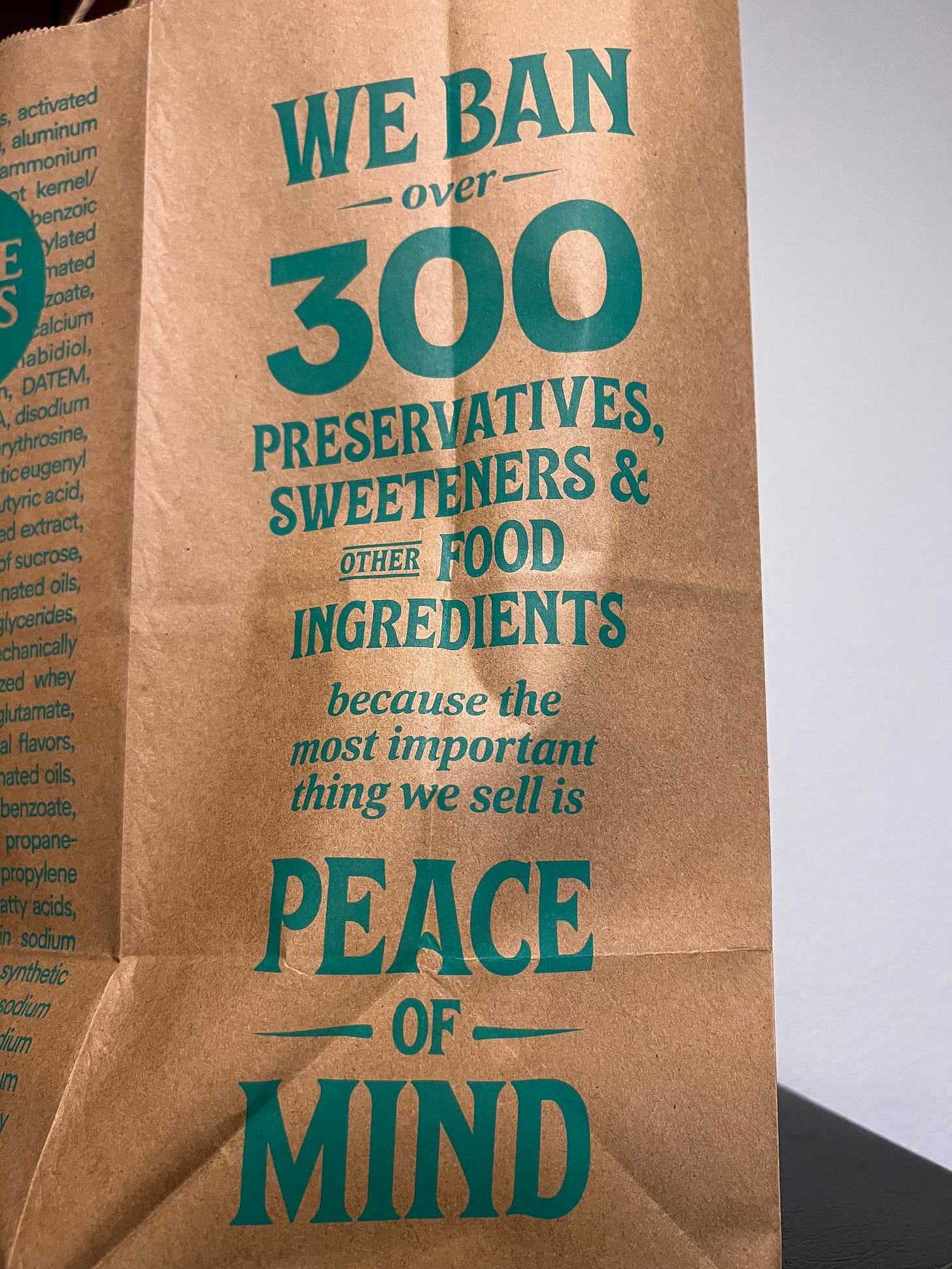

BFY grocers have tried to take the place of ineffective regulations on food quality and transparency. They are also well-positioned to take advantage of regulations on ultra-processed food labeling which are being considered or approved in dozens of states, such as California. While FDA GRAS (generally recognized as safe) has come under fire for being wholly inadequate in regulating what types of ingredients and products come to market, BFY grocers have segmented off a section of the marketplace with clear and transparent sourcing standards. Whole Foods is the largest and most visible retailer, marketing their commitment to quality standards right on their shopping bags. Natural Grocers takes it even further, with stricter sourcing standards on produce and animal products. Mom’s sells only organic produce and their center store assortment is on par with Whole Foods and most co-ops. About 98% of the produce at PCC is organic and they maintain their own sourcing standards team.

When the private sector steps in like this to take the place of a lax regulatory system, it means they are marketing these standards to build their customer base, grow market share and generate profits. On the one hand, this has a positive knock on effect in supply chains, in that producers willing to abide by such rubrics have clear market signals and the potential to grow and thrive. But if such standards are used to justify premium prices and high margins, they also increase inequality and food apartheid, and decrease healthy food access.

Public sector supply chains have addressed this contradiction head on by applying values based purchasing to supply chains, assuring good food, on par with Whole Foods or Sprouts, is free or low cost at point of consumption, such as free school lunches. And food activists and regulators are finally taking a serious look at GRAS reforms.

But BFY standards do not take the place of food safety regulations and inspections. Their supply chains are as vulnerable to allergens or pathogens as any grocers, and all BFY retailers have sold products that have sickened or inadvertently led to the deaths of customers. With Trump-era rollbacks on food safety staffing, reporting and inspection, BFY grocers will face growing risks due to the federal shortfalls in regulatory systems. This private sector substitution of a robust regulatory framework is also a consistent theme in post-Cold War, globalized and neoliberal economics.

BFY’s Fresh Focus.

BFY grocers all focus on and over index on their fresh assortment. Whole Foods sources higher spec produce than the rest of the market and their produce percent of store sales is twice as high as many supermarkets. While they have increased their conventional produce sales share, they still outpace the market on percent of organic produce sold, at 54%. Whole Foods was also an early supporter of the Coalition of Immokalee Workers Fair Food Program and other social responsibility programs. They have also put an outsized effort into their egg, meat, poultry and seafood supply chains in terms of animal welfare, hormone/antibiotic-free, traceability, food safety and fair contracts with growers. As they have gotten larger, they have moved away from some of their smaller producers, but other chains like Natural Grocers have picked up the slack. Natural Grocers’ baseline sourcing for animal products is pasture-raised and hormone/antibiotic free, and their meat, eggs and dairy over index in grassfed and regenerative products. They steer clear of the factory farmed cage free “all-natural selection” at Whole Foods. And their produce is not always the freshest or highest quality, but it is 100% organic.

Sprouts has also shifted their produce sourcing to increase their organic share and focus on higher quality and spec varieties. Their meat and poultry standards are not far off of Whole Foods and they have also been rolling out more regenerative and grassfed lines. Fresh Market does not sell as much organic, but they lean on higher quality and visually appealing produce, and their perimeter merchandising has more of a neighborhood specialty grocer feel. PCC sells some of the most exceptional produce in the U.S, it is all organic and much of it regionally sourced from the Pacific Northwest and their full service meat cases are staffed by unionized meat cutters. Except for Natural Grocers, all of these chains have full service meat cases and skilled meat cutters on staff during business hours.

BFY Vs. Local.

Despite this focus on fresh, few of these BFY chains have maintained a big focus on local sourcing and supply chains. Whole Foods still has a remnant local foraging program, with a handful of committed, long term employees helping source and mentor small brands to get into stores, expand distribution and navigate the gauntlet of retail and wholesale promotional, marketing and category management challenges. Their impact is more deep than broad, and their efforts are focused on a small selection of store level and metro market growth of locally grown or made products. Local has instead remained the strategic domain of consumer cooperatives and independent natural food stores, who still commit substantial, year-round space to local products on grocery shelves and in perimeter coolers. But by and large, the admonishments and exhortations of Omnivore’s Dilemma-era locavores could not withstand the brutal consolidation, cost inflation and pricing pressures of the grocery marketplace. Local has lost the cache that it had in the early 2000s as a sales driver and now feels much more like a “nice to have” than a “need to have” for most BFY grocers. It is mostly a marketing angle, not a means of building regional food system resilience as it once envisioned.

BFY Vs. Labor Vs. Pricing.

BFY grocers are aware of their premium price perception and have each take steps to mitigate their price gaps to the rest of the marketplace, but it hasn’t always been pretty. In particular, Whole Foods has closed the price gap on key value items (milk, bread, butter, eggs, cheese, ground beef) to most competitors by reducing staffing of store employees, cutting back the ratio of full time to part time staff, avoiding union contracts and reducing regional and corporate administrative teams. In effect, lower prices and greater private label share have been funded by a rollback in store level labor.

Natural Grocers and Mom’s keep store staffing to a minimum and run labor budgets at least 5% lower than most grocers, and invest these savings in lower prices. It is no coincidence that many of these BFY grocers tend to be allergic to unions and the legally binding wage, compensation and pension costs that would hamper their ability to invest in pricing as the market dictates. While some BFY grocers pay above market hourly wages, they rarely pay living wages or give staff a full 40 hours of shift work every week.

BFY grocers also tend to under index in private label penetration and have each launched hundreds of new store brand items in the past few years to bridge price gaps to discounters and mass merchants. While BFY grocers will stock higher attribute private label lines, they are also providing low price, low margin conventional items to compete with mass market chains and discounters like Walmart, Kroger and Aldi. This includes grocery co-ops, which use wholesaler private labels such as Field Day, Cadia, Full Circle and Wild Harvest. These store brands are defensive plays that define their price perception and show willingness to match assortment and price with the biggest chains. BFY grocers will always have some unique, innovative items under their own brand name, but the vast majority of their private label sales are every day, key value items and pantry loaders that most people can’t live without. Private label sales are therefore a hedge against food apartheid, even in the most premium parts of the marketplace.

BFY Inside Income.

BFY grocers are not cheap dates for suppliers. They are expensive to do business with. Rent seeking is an increasingly important part of their bottom lines. Whole Foods requires slotting fees of one case per sku per store for every new item launch, charges over $100k for off shelf display placements, in addition to requiring suppliers to fund in-store sale markdowns in the form of off invoice, manufacturer chargeback or scanback discounts, as well as team member discounts on sale items, Amazon Prime Discounts, a 3% in store merchandising fee to fund outsourced labor that will do the work no longer done internally due to store staffing cuts, as well as a 2.5% UNFI fee on all applicable items. Sprouts likewise requires slotting, charges exorbitant display placement fees, requires suppliers fund in-store sale markdowns and “buy one get one” discounts on offshelf displays and has asked suppliers to fork over a 6% everyday discount that will be pocketed and not be reflected in lower shelf prices, but justified by the chain’s sales growth, store growth and growing market share.

BFY grocers could not be profitable without these inside income streams. These inside income streams are also materially important to the slim margins of the wholesalers that supply these grocers the bulk of such products.

For suppliers, it means they must budget a disproportionate amount of their trade and marketing spend, sometimes upwards of 25% of gross revenue, just to stay in play. Revenue grabs warp the marketplace and favor brands with the deepest pockets, and not the most interesting, highest quality or best tasting.

Independent and cooperative grocers, including consumer and retailer-owned cooperatives tend to not have as much rent-seeking, and this is probably a reason why they can support so much more local products. A higher proportion of their fees just cover their operational and administrative costs.

BFY Vs. Inflation.

BFY grocers have benefitted from price inflation and the resulting lower price gaps between “cheap” commodity products and more premium and organic items. This is not good news for consumers on SNAP or who are otherwise stretched thin. But it has helped the price perception of BFY grocers. While their assortment did face inflationary pressures, especially in 2021 and 2022, it wasn’t as much as what conventional products experienced. And while they did pass higher costs onto consumers, there is not as much data to illustrate the type of price gouging and profiteering that was done by packaged food conglomerates and mass merchants from 2021-2024.

All in all, beef has gone up 70% in price, eggs have gone up 160%, coffee has gone up 36%, chocolate has gone up 48%, cookies and crackers have gone up 40% and pet food has gone up 50%. On average, the top 10 most popular grocery categories have gone up 60% in just 5 years. It is no wonder that unit volumes are down almost 5%. The grocery industry is selling less product than 5 years ago.

The promise of industrial food was that it would be cheap, abundant, ubiquitous, and that has been broken by post-pandemic profiteering and supply chain crises. But it’s been a win for BFY grocers whose more sustainable assortment is closer to that of a “true cost” of production. But with more inflationary pressures at hand in beef, chocolate, coffee and tinned goods, and slower consumption volumes that mean retailers can’t pass on cost hikes as guilelessly, even BFY grocers may get pinched.

BFY Innovation Drivers.

BFY grocers have also put a huge focus on new product innovation. In the past, Whole Foods was the early adapter and would take risks on new products like Icelandic skyr, New Zealand lamb, probiotic sodas or cassava tortilla chips. Whole Foods also had a robust but unwieldy regional and local purchasing teams for many years that sourced, mentored and scaled thousands of small enterprises into household names- Purely Elizabeth, Siggi’s, Justin’s, Siete, Lesser Evil, Bear Naked, Applegate, Lily’s, Dave’s Killer Bread.

These days, Whole Foods is a bit more risk averse and willing to watch data trends before going all in. The chain actually launches more products every year than it used to, sometimes upwards of 2,000 products a year. But the attrition and failure rates are pretty high due to the competition on shelf from incumbent brands and expanded private labels. In produce, Whole Foods has partnered with Row 7 to launch exclusive, high quality and flavor-forward varieties of popular fruits and vegetables. In center store, the retailer has championed regenerative organic products and has industry leading “global flavors”, seasonings, and salty snack assortments, as well as one of the most sustainable and traceable chocolate bar category sets in the world, an assortment that has been copied by other BFY grocers, cooperatives and indies, featuring a bean to bar and fairly traded selection that even Lina Khan would likely approve of.

Sprouts has taken on much of the new item risk that Whole Foods has shed, with an aggressive new product rotation featured on in-store kiosks. These new suppliers are exempt from the rent-seeking income streams while they are getting started, but not all of them survive to become regular suppliers. While Sprouts has rapidly expanded private label share, they have also found space on shelf for thousands of new brands over the past few years, helping give new products an alternative to launching at Whole Foods, while also reaching a national audience. Specialty chain Fresh Market and their wholesale partner Chex Foods, as well as regional grocers such as Wegmans, Fairway, Mom’s, PCC and many cooperative and independent natural food retailers also continue to lead the market in product innovation, especially on various sustainability, health and wellness trends.

BFY Grocers Punch Up.

And finally, BFY grocers punch above their weight class when it comes to the impact they are having in the marketplace.

Their assortment is becoming more populist and accessible due to competition from regional grocers, such as store-within-a-store concepts in value-priced, regional mass merchants such as HyVee, Wegmans, Woodmans and HEB. While much of their assortment is comparable to any Kroger or Ahold-Delhaize banner, these chains cordon off a couple aisles with allergen-free, organic, non-gmo, and keto or paleo products, with matte-finished packaging, contemporary fonts and designs, and shorter ingredient decks, and integrate many such items into their mainline assortment as they become more popular. These are the exceptions that prove the rule, that BFY products are becoming mainstream due to the growth of BFY grocers, and even these regionally dominant chains are dedicating significant shelf and floor space to showcase these products to a more mainstream clientele.

It is not just the regional mass merchants integrating BFY products sections into stores. BFY is affecting everything.

The wave of mergers and acquisitions in consumer packaged goods companies such as Mars-Kellanova, Kellogg’s-Ferrero, Pepsi-Siete/Poppi, and the Kraft-Heinz disaggregation, are as much a result of cost pressures and consumers moving away from incumbent brands while embracing BFY products and less expensive private label products. This did not happen overnight.

Twenty years ago, Safeway saw the writing on the wall and launched the first mass market organic product line with Safeway Organics. Over a decade later, Kroger analyzed their dunnhumby customer data and saw that their clientele wanted healthier and more sustainable products. Kroger realized they had a huge opportunity to steal share from Albertsons, Whole Foods and Trader Joes, fence off Walmart, and established a value tier for organic, BFY and minimally processed packaged goods, and called it Simple Truth. It quickly became one the most successful store brand launches ever.

Within a couple years, mass market organic and BFY private label brands flooded the market from HEB, Ahold-Delhaize banners, Shoprite/Wakefern, Topco, C&S, KeHe, UNFI and most other grocers and wholesalers. And two years ago, Walmart saw a similar generational shift in their customer preferences and launched bettergoods. The launch was so successful they applied the learnings and announced they would be banning artificial colors from all Walmart store brands, including Great Value, a $70 billion behemoth with over 80% household penetration, the second largest packaged food brand after Kirkland Signature. This was the momentum from BFY grocers and the changes in customer habits that they precipitated, enabled and encouraged for decades.

This is why BFY grocers are the most important story in food.

peace.